A Farewell to Keith Critchlow

Keith Critchlow, architect of the Krishnamurti Centre, died in April 2020, aged 87. Keith was an artist, author, professor of art and architecture, and expert in sacred geometry. He was also a frequent visitor to the Centre, which he was asked to design after an unusual interview at Brockwood in 1985.

Keith Critchlow, architect of the Krishnamurti Centre, died in April 2020, aged 87. Keith was an artist, author, professor of art and architecture, and expert in sacred geometry. He was also a frequent visitor to the Centre, which he was asked to design after an unusual interview at Brockwood in 1985. Keith spoke of this at a presentation given to Friends of Brockwood Park in the Krishnamurti Centre in 2016. He also recalled his first encounter with Krishnamurti, when aged just 13 he was taken by his father to a talk given in Wimbledon. He did not recall the talk’s content, but remembered the impressive manner in which Krishnamurti dealt with aggressive opposition from the audience.

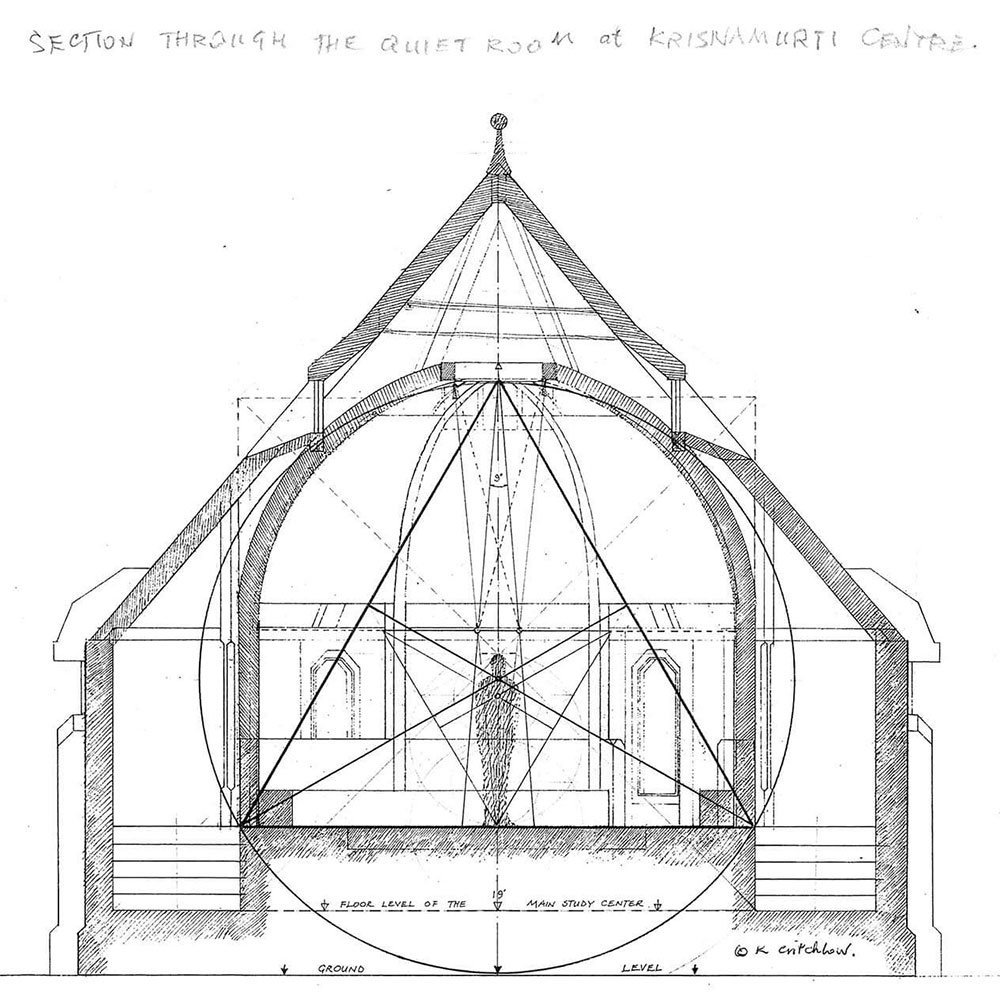

In his 2016 presentation, Keith spoke about the stage of designing the Centre where he concentrated on its intrinsic nature as a whole:

My own convictions growing out of the study of many, many older Building Wisdom systems was that a ‘seriously intentioned’ building needs to follow, in some way, the human form. This was expressed in different ways in the world. ‘K’ expresses it beautifully and profoundly in his statement: ‘You are the world and the world is you… On this basis I did a drawing of a human body sitting in what is generally known as the lotus position of legs folded up underneath the torso, with the hands resting on the knees. Which seemed appropriate for the present circumstance, the position of a person in study, contemplation or even meditation.

Krishnamurti did not live to see the Centre built, but at Brockwood in September of 1985, Keith had a meeting with him and small group to discuss the design of the Centre. The following is an extract from the unpublished transcript of this meeting. The topic of discussion is the Quiet Room at the Centre:

Krishnamurti: (Looking at the plans for the Centre) That is the silent room.

Keith Critchlow: That is the silent room, exactly.

K: Yes. I see, you are working out from there.

KC: From silence, yes, yes, to the greatest activity which would take place, in a sense. But then we’ve sealed it off here and here with the staff accommodation. In other words, people who are here more permanently will seal the end off. Otherwise there is the danger that it will dissipate off. So that sort of holds everything in, and in the end you’re containing everything in a triangle.Now this is again rather technical but regarding the proportions, there is a very important way in which proportions work between the eight, which is the product of a square. That says ‘4’ to me, because of earth, air, fire and water, and all the things to do with worldly things. And so then the 8 here is a way of complementing that, because it is another square coming this way, and so we have a geometry of 8, and inside that a geometry of 12. And the 12 is to do with the rhythm of the day, the hours of the day and the months of the year. And we may design the little garden [in the courtyard] on a pattern like this.

K: I understand.

KC: This is a summary really of what we just have been through. What it amounts to is that these harmonics will be invisible – they are rather like silent music – but these ones will be the visible ones. This is the triangle that Plato said was the most beautiful triangle in the world. But he was clever enough to say that if somebody finds a more beautiful one then the victory is his. So he wasn’t being dogmatic. (Laughter) But for Plato to claim one triangle as the most beautiful… So we are going to proportion the rooms with this system and we are going to proportion the body of the building with the octagon.

Scott Forbes: You are going to proportion the roofs according to this?

KC: According to the spirit of 3.

Peter Gilbert: So we are working with a root 4 above and a root 2 below.

SF: Because the octagon works out as a root 2?

KC: Yes, this is what is called a root 2 rectangle. This is the earliest proportion we’ve got in Britain. At Stonehenge, the first four stones were placed on those points of an octagon, the Station Stone rectangle. All the rest of Stonehenge is inside there. But the overall perimeter of Stonehenge is these four stones for calculating the solstice and equinox. And if you divide this by that, you get a perfect square in the middle and two root 2 rectangles. So this distance here is root 2. And that is the same as a square, where the diagonal is the square root of 2. And all our musical tuning is now done on a square root of 2. A lot of people say it’s not correct – we gave up Pythagoras for this kind of tuning. Anyway, it is a musical tuning. It is also the only dialogue that Plato devoted completely to one proportion, the Meno dialogue, which is one of the most important ones on Plato putting forward his theory of recollection, that everything is recollection. Maybe Krishnaji completely objects to that. (Laughs)

K: No, no. I understand.

KC: I don’t know…

K: No, don’t bother about me.

KC: No, okay. I mean, I get a lot of inspiration from Plato (laughs).

K: Yes sir. Go ahead.

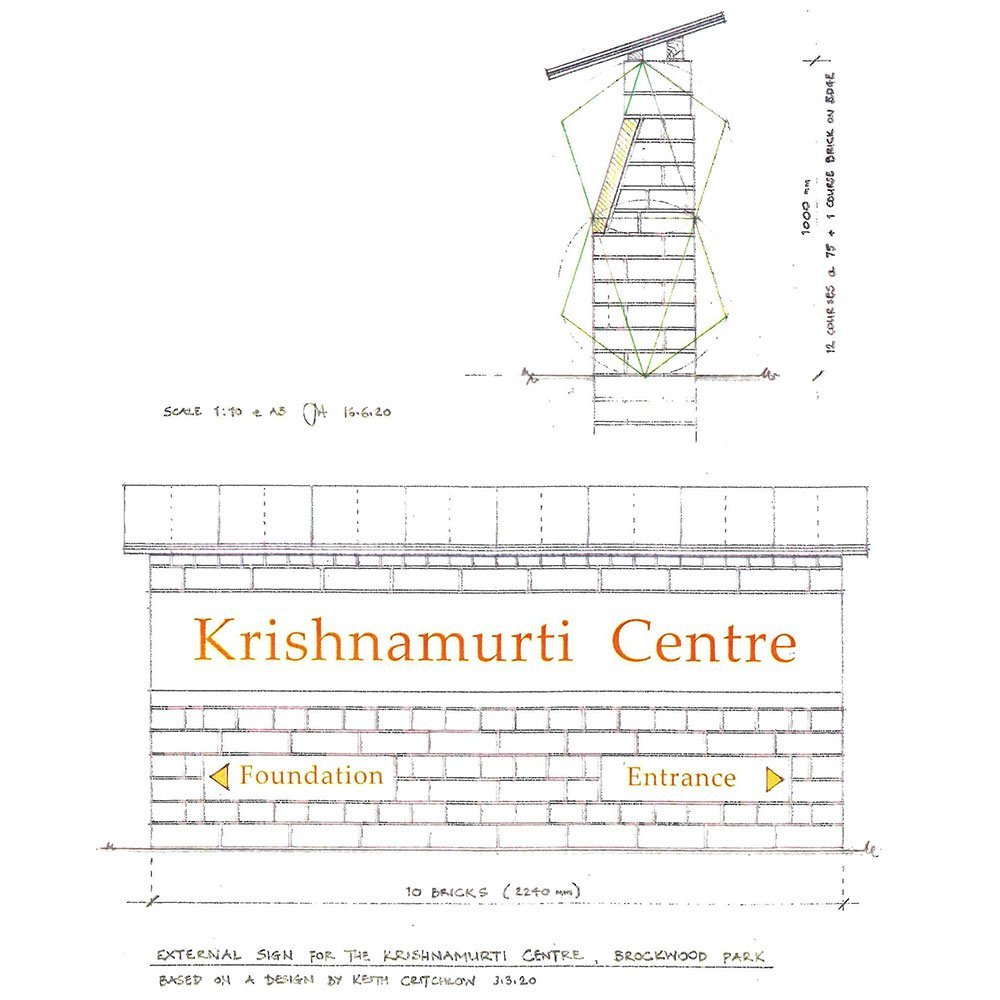

Keith made a final visit to the Centre in November of 2019, staying two nights and having several meetings with staff about the care of the building and possible improvements. He was asked to produce a design for a sign for the Centre, intended to be as elegant and timeless as the building itself. The drawing below, by Keith’s long-time collaborator, architect Jon Allen, is based on Keith’s sketches and, funding and planning permission permitting, will be constructed at the entrance to the car park of the Centre. The text will be in stone and the plinth will add a small, but significant final piece, to Keith’s sublime legacy to Brockwood Park and the teachings.