You canNOT BE attached to a living thing any more than you can be attached to the river or the sea because the living thing is moving, eternal, in a state of continual motion. So when you say you are attached to your son or daughter, your husband or wife, if you can very carefully look within yourself you will see that you cannot be attached to a living person because that person is constantly changing, moving, in a state of turmoil. What you are attached to is your picture of that person.

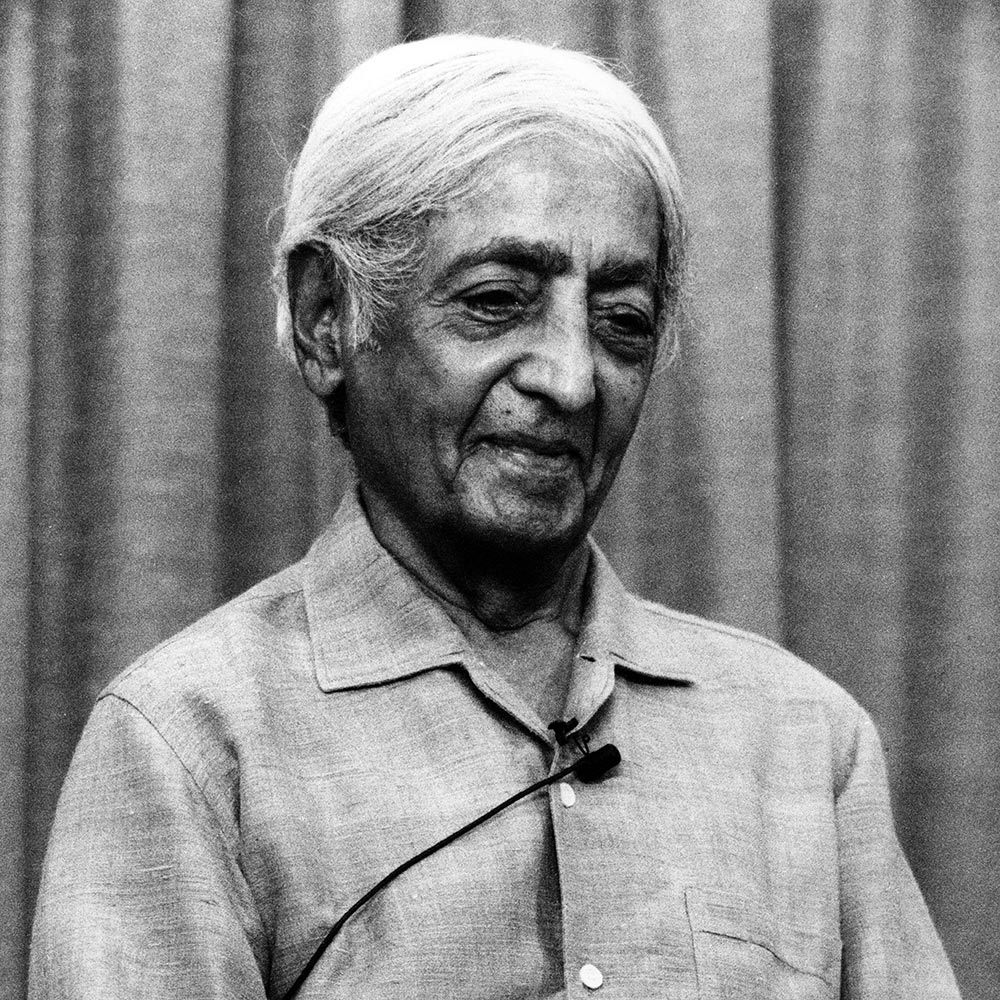

Krishnamurti in Bombay 1958, Talk 4

Where There Is Attachment There Is No Love

Attachment is the outcome of fear, of various forms of loneliness, emptiness.

If you will experiment with this you will see. Merely to cultivate detachment becomes so very superficial. If you are detached, then what? But when there is awareness, you will see that where there is attachment there is no love; where there is attachment there is the desire for permanency, for security, for self-continuance – which doesn’t mean we should pursue self-destruction. And seeing that, then the problem of attachment becomes extraordinarily significant and wide. Merely to run away from attachment because so much pain is involved can only lead to superficial love, superficial thinking. And most of us who are practising virtue, the virtue of detachment, of non-greed, of non-violence, do lead superficial lives: the life of ideas, the life of words.

If one is aware of the whole problem of attachment, one will begin to find out the extraordinary depths of it, how the mind is attached to the experience of yesterday with its pain or with its pleasure, how the mind clings to it. One cannot be free of the experience of both the pleasure and the pain until one is really aware. In that awareness in which there is no choice or reaction, the mind can go very deeply. The mere practice of any virtue can only lead to respectability, which is what most people desire, for respectability identifies us with society. We all desire to be recognized as being something, great or little, this or that, and to that idea we are attached. We may want to detach ourselves from people because it causes pain, while the idea to which we are attached does not. But to really understand this whole problem of attachment, to tradition, to nationality, to custom, to a habit, to knowledge, to opinion, to a saviour, to all the innumerable beliefs and non-beliefs, we must not be satisfied merely to scratch the surface and think we have understood the problem of attachment when we are cultivating detachment. Whereas if we do not try to cultivate detachment, which only becomes another problem, if we can just look clearly at attachment, then perhaps we shall be able to go very deeply and discover something entirely different, something which is neither attachment nor detachment.

Krishnamurti in London 1955, Talk 1

Video: Desire and Fear

Love Knows No Attachment

I would like you to investigate with me into the problem of attachment, because it is very important to understand. You are attached. You are attached to things – a car, your property, a dress; or you are attached to a person – your wife, your child, your friend; or you are attached to an idea of God or no God, of reincarnation. What does this attachment mean? One can understand to a certain extent being attached to a watch or a house, even though they are dead things, but the attachment to a person or to an idea is much more complicated. Attachment seems to be invariably to dead things. Is the attachment to the wife, the husband, the son, to a living thing or really to a dead thing? Are you attached to a living person or the picture you have made of a living person? And is not that picture a dead thing? What are you attached to? Not the living person but the idea, the memory of the pleasures and experiences you have had from that person. Can you be attached to a river? You may have a memory of a particular river, but you cannot be attached to the waters; the river is moving swiftly, it is in a constant state of movement and what you are attached to is a picture which the word river awakens – somewhere where you had pleasure, amusement, a quiet evening by the riverside. But you cannot be attached to the movement of that water.

Are you attached to a living person or the picture you have made of a living person?

If we follow this carefully we are going to find out how through attachment we are destroying feeling, because all our attachment is to dead things. You can never be attached to a living thing any more than you can be attached to the river or to the sea because the living thing is moving, eternal, in a state of continual motion. So when you say you are attached to your son or daughter, your husband or wife, if you can very carefully look within yourself you will see that you cannot be attached to a living person because that person is constantly changing, moving, in a state of turmoil. What you are attached to is your picture of that person. When I say I am attached to my son, it is because through him I immortalize myself, expect him to keep up my name. I say I may have been a failure but he will be successful, he will be more ambitious than I have been, and so I identify myself with him – the “him” being a picture. But the picture is a dead thing. So look what the mind is doing, it is creating pictures and attaching itself to dead things!

When you say you are attached to an idea, what are ideas? Look sir, you are a Hindu, a Muslim, a Christian, a Buddhist, an atheist – whatever you are, you have that idea firmly fixed in your mind, as it is firmly fixed in the mind also of the socialist or capitalist. But ideas can never be living things, they are conclusions, reactions, dogmas impressed on your mind from childhood through propaganda, compulsion, education and communication. And have you not found how astonishingly difficult it is to free the mind from an idea? To free the Hindu mind from ideas of reincarnation, karma and all the rest of it, is almost impossible. So again you can see that a mind attached to ideas, conclusions and beliefs is attached to dead things. It is very difficult to cease being attached because we do also love people. But where there is attachment can there be love? Or is love something vital, creative, moving, a feeling which cannot exist together with what is dead? How arduous and difficult it is to see this fact! It requires a great deal of insight, a great deal of energy and comprehension to see that the mind is everlastingly attaching itself to dead things and that such a mind is itself dead.

So you begin to see that love knows no attachment. That is a hard thing to swallow, but it is a fact. And because our minds are so attached to dead things problems arise. Then we try to cultivate detachment, which is attachment in a different cloak and therefore still in the field of death. Do observe in yourself how dead we are, how we have destroyed the bubbling feeling. The earth is not a dead thing, but when you are attached to something you call “India” which is just a symbol of a small part and not the earth itself, then you are clinging to something which is dead. Therefore your nationalism is merely a flirtation with death; it has no depth, no vitality. But the feeling for the earth itself, not my earth or the Russian, American or English earth, that has a living quality.

So can we not understand, feel, see, that where there is attachment there is death? After all, when you are doing the same thing every day, getting up at the same time, repeating the same routine, going to the office and so on, it becomes a custom, a tradition, a habit, and so your mind becomes dull. You may pass a lovely sunset or sunrise, a single tree alone in a field, and no depth of feeling is aroused because habit has taken the place of feeling and your mind becomes attached to habit, and it objects to being shaken. The mind objects to change, and so the mind is destroying itself through its own attachments to dead or dying things.

If you have really understood all this, not merely verbally or intellectually, but if you feel deeply that this is really a very serious thing, then you will see that you can go to the office, take a bus, function in everyday life with a different quality, a new quality of mind. After all, you cannot stop doing your regular job, living your daily life. Now it is a routine to which you are attached and when you are attached to the fountain that holds the water you cannot move with the living water. To see the truth of this requires not only insight, clarity of thought, precision of mind, but also the sense of beauty. If you have understood, you will see that attachment has no meaning anymore. You do not have to struggle to be free of it; it drops away like a leaf in the wind. Then your mind becomes extraordinarily alive, sharp, precise, no longer confused. But you are attached to action and you want immediate answers. You have to decide what to do tomorrow and that is much more compelling, much more urgent to you than this inquiry and the feeling of this whole quality of comprehension, understanding, beauty and love. So your actions are always leading to death, death being confusion, misery, suffering and toil. If you see a man who only wants immediate action, immediate solution, what can you do for such a man who is pursuing death and insists on doing it? I am afraid most of us are like that.

The mind is destroying itself through its attachments to dead things.

So if you and I have really truthfully and honestly asked ourselves how to awaken this feeling, then we shall have seen that any form of attachment is a dead thing, and that this deadly quality of attachment, to things, to people and to ideas, invariably leads to the grave. In perceiving this you will see that your desire for immediate action has an answer at a totally different level, and the answer will be true and it will be practical.

For most of us the day to day action of habit has become all-important, so that we never see the horizon but are always doing something. You can only have the explosion of feeling when you understand this whole process of yourself and your attachments. If you can explore, examine, look into this thing called attachment, then you will begin to learn, and it is learning that will break up the dead things; it is learning that will give the feeling to action. You may make a mistake in that action, but that mistake is a constant process of learning. To act means that you are trying to see, to find out, to understand, not merely trying to produce a result, which is a dead result. Action becomes very small and petty if you do not understand the centre, the actor. We separate the actor from the action; the “I” always does that and so becomes a dead thing. But if you are beginning to understand yourself, which is self-knowledge, which is learning about yourself, then that learning is a beautiful thing, so subtle, like living waters. If you understand that, and with that understanding act, not with the action of thought but through the very process of learning, then you will find that the mind is no longer dead, no longer attached to dead and dying things. The mind then is extraordinary; it is like the horizon, endless, like space, without measure. Such a mind can go very deeply and become that which is the universe, the timeless. From that state you will be able to act in time, but with a totally different feeling. All this requires not chronological time but the understanding of yourself, which can be done immediately. You will know then what love is. Love knows no jealousy, no envy, no ambition, and has no anchorage; it is a state in which there is no time, and because of that, action takes on a totally different meaning in our daily existence.

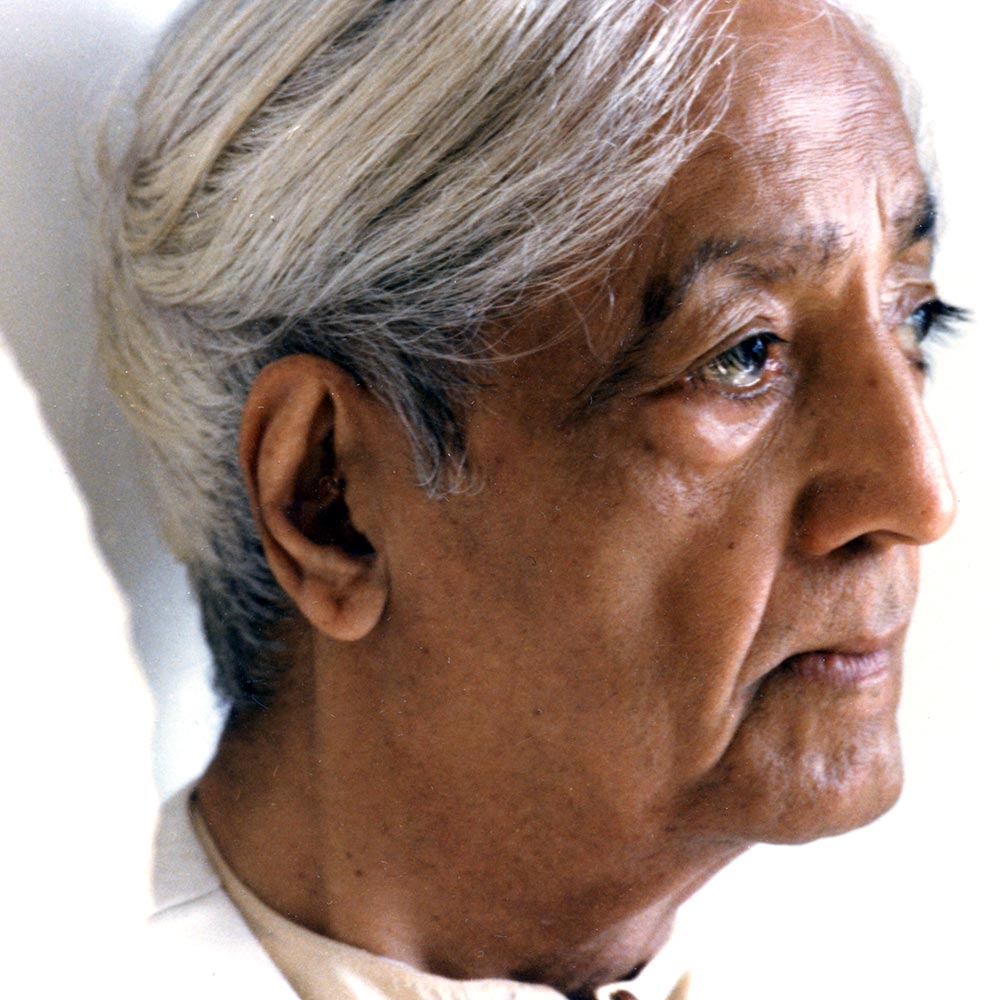

Krishnamurti in Bombay 1958, Talk 7

Audio: Why Is the Mind Attached?

How Can We Be Free of Attachment?

Question: Attachment is the stuff of which we are made. How can we be free from attachment?

Krishnamurti: Surely attachment is not the problem, is it? Why are you attached, and why do you want to be detached? Why is there this constant strife between attachment and detachment? You know what is meant by attachment – the desire to possess a person, to possess things. Why are you attached? What would happen if you were not attached? Attachment becomes a problem only when there is the pursuit of detachment, only when that which is attached is not understood. Why are you attached to your wife, to your husband, to your money, to your house, your property or your ideas? Because without that person you are lost, you are empty; without property, without a name, you are nothing; and without your bank account, without your ideas, what are you? An empty shell, aren’t you?

One who is afraid of emptiness, of being nothing, is attached.

So, because you are afraid of being nothing you are attached to something. And being attached, with all its problems, with its fears, cruelties, anxieties and frustrations, you try to become detached, you try to renounce property, your family or ideas. But you have not really solved the problem, which is the fear of being nothing. And that is why you are attached. After all, you are nothing. Strip yourself of your titles, your qualifications, your profession and qualities, your houses, properties and jewels, and what are you? Knowing inwardly that there is an extraordinary emptiness, a void, a nothingness, and being afraid of it, you depend, you are attached, you possess; and in that possession, there is appalling cruelty. You are not concerned about another, you are only concerned about yourself. So, because you are afraid, because there is fear of that emptiness, you are willing to kill another, to destroy mankind.

Why not accept the obvious, which is that you are nothing? Not that you should be nothing, but that you are actually nothing. When you do accept it, there is no renunciation, neither attachment nor detachment. You simply don’t possess, and then there is a beauty, a richness, a blessing that you cannot possibly understand as long as you are afraid of emptiness. Then life is full of significance, then life becomes really a miracle. But one who is afraid of emptiness, of being nothing, is attached, and with attachment there arises the conflict of detachment, the conflict of renunciation, and all the appalling misery and cruelty that comes with attachment and dependence. A man who is nothing knows love, for love is nothing.

Krishnamurti in Bombay 1948, Talk 11

Video: Finding Out What Love Is

What Is Freedom?

I would like to consider with you the vast and complex problem of freedom. To inquire into that problem, to commune with it, to go into it hesitantly, tentatively, requires a very sharp, clear and incisive mind, a mind that is capable of listening and thereby learning. If you observe what is taking place in the world, you will see that the margin of freedom is getting narrower and narrower. Society is encroaching upon the freedom of the individual. Organized religions, though they talk about freedom, actually deny it. Organized beliefs, organized ideas, the economic and social struggle, the whole process of competition and nationalism – everything around us is narrowing down the margin of freedom, and I do not think we are aware of it. Political tyrannies and dictatorships are implementing certain ideologies through propaganda and so-called education. Our worship, our temples, our belonging to societies, to groups, to political parties, all this further narrows the margin of freedom. Probably most of you do belong to various societies or groups you are committed to, and if you observe very closely you will see how little freedom, how little human dignity you have, because you are merely repeating what others have said. So you deny freedom, and surely it is only in freedom that the mind can discover truth, not when it is circumscribed by a belief or committed to an ideology.

I wonder if you are at all aware of this extraordinary compulsion to belong to something? I am sure most of you belong to a political party or a certain group or organized belief. You are committed to a particular way of thinking or living, and that surely denies freedom. I do not know if you have examined this compulsion to belong, to identify oneself with a country, with a system, with a group, with certain political or religious beliefs. Without understanding this compulsion to belong, merely to leave one party or group has no meaning, because you will soon commit yourself to another. Have you not done this very thing, leaving one “ism”, you go and join something else. You move from one commitment to another, compelled by the urge to belong to something. Why? I think it is an important question to ask oneself. Why do you want to belong? Surely it is only when the mind stands completely alone that it is capable of receiving what is true; not when it has committed itself to some party or belief. Please do think about this question, commune with it in your heart. Why do you belong? Why have you committed yourself to a country, to a party, to an ideology, to a belief, to a family, to a race? Why is there this desire to identify yourself with something? And what are the implications of this commitment? It is only one who is completely outside that can understand, not one who is pledged to a particular group or who is perpetually moving from one group to another, from one commitment to another.

There is dignity as a human being only when one has tasted this extraordinary thing called freedom.

Surely you want to belong to something because it gives you a sense of security, not only socially but also inwardly. When you belong to something you feel safe. By belonging to this thing called Hinduism you feel socially respectable, inwardly safe, secure. So you have committed yourself to something in order to feel safe, which obviously narrows down the margin of freedom.

Most of us are not free. We are slaves to Hinduism, to communism, to one society or another, to leaders, to political parties, to organized religions, to gurus, and so we have lost our dignity as human beings. There is dignity as a human being only when one has tasted, smelt, known this extraordinary thing called freedom. Out of the flowering of freedom comes dignity. But if we do not know this freedom we are enslaved. That is what is happening in the world, and I think the desire to belong or to commit ourselves to something is one of the causes of this narrowing down of freedom. To be rid of this urge to belong, to be free of the desire to commit oneself, one has to inquire into one’s own way of thinking, to commune with oneself, with one’s own heart and desires. That is a very difficult thing to do. It requires patience, a certain tenderness of approach, a constant and persistent searching into oneself without condemnation or acceptance. That is true meditation, but you will find it is not easy to do, and very few of us are willing to undertake it. Most of us choose the easy path of being guided, being led; we belong to something and thereby lose our human dignity. Probably you will say, ‘I have heard this before, he is on his favourite subject,’ and go away. I wish it were possible for you to listen as if you were listening for the first time, like seeing the sunset or the face of your friend for the first time. Then you would learn, and thus learning you would discover freedom for yourself, which is not the so-called freedom offered by another.

So let us inquire patiently and persistently into this question of what is freedom. Surely only one who is free can comprehend the truth, which is to find out if there is an eternal something beyond the measure of the mind; and one who is burdened with their own experience or knowledge is never free, because knowledge prevents learning. We are going to commune with each other, to inquire together into this question of what is freedom and how to come by it. And to inquire there must obviously be freedom right from the start, otherwise you cannot inquire. You must totally cease to belong, for only then is your mind capable of inquiring. But if your mind is tethered, held by some commitment, whether political, religious, social or economic, then that very commitment will prevent you from inquiring because for you there is no freedom.

Do please see for yourself the fact that the very first movement of inquiry must be born of freedom. You cannot be committed and from there inquire, any more than an animal tied to a tree can wander far. Your mind is a slave as long as it is committed to Hinduism, to Buddhism, to Islam, to Christianity, to communism, or to something it has invented for itself. So we cannot proceed together unless we comprehend from the very beginning, from now on, that to inquire there must be freedom. There must be the abandonment of the past, not unwillingly, grudgingly, but a complete letting go.

After all, the scientists who got together to tackle the problem of going to the moon, were free to inquire, however much they may have been slaves to their country. I am only referring to that peculiar freedom of the scientist at a research station. At least for the time being, in his laboratory, he is free to inquire. But our laboratory is our living, it is the whole span of life from day to day, from month to month, from year to year, and our freedom to inquire must be total, it cannot be a fragmentary thing, as it is with technical people. That is why, if we are to learn and understand what freedom is, if we are to delve deeply into its unfathomable dimensions, we must from the very start abandon all our commitments and stand alone. And this is a very difficult thing to do.

The other day in Kashmir, several sannyasis said to me, ‘We live alone in the snow. We never see anybody. No one ever comes to visit us.’ And I said to them, ‘Are you really alone, or are you merely physically separated from humanity?’ ‘Oh yes,’ they replied, ‘we are alone.’ But they were with their Vedas and Upanishads, with their experiences and gathered knowledge, with their meditations and mantras. They were still carrying the burden of their conditioning. That is not being alone. Such men, having put on a saffron cloth, say to themselves they have renounced the world, but they have not. You can never renounce the world because the world is part of you. You may renounce a house, some property, but to renounce your heredity, your tradition, your accumulated racial experience, the whole burden of your conditioning, this requires an enormous inquiry, a searching out, which is the movement of learning. The other way, becoming a monk or a hermit, is very easy.

What is the state of the mind that is free to inquire?

So do consider and see how your job, your going from the house to the office every day for, 40 years, your knowledge of certain techniques as an engineer, a lawyer, a mathematician, a lecturer, how all this makes you a slave. Of course, in this world one has to know some technique and hold a job; but consider how all these things are narrowing down the margin of freedom. Prosperity, progress, security, success, everything is narrowing down the mind, so that ultimately, or even now, the mind becomes mechanical and carries on by merely repeating certain things it has learnt.

A mind that wants to inquire into freedom and discover its beauty, its vastness, its dynamism, its strange quality of not being effective in the worldly sense of that word, such a mind from the very beginning must put aside its commitments, the desire to belong, and with that freedom it must inquire. Many questions are involved in this. What is the state of the mind that is free to inquire? What does it mean to be free from commitments? Is a married man to free himself from his commitments? Surely where there is love there is no commitment; you do not belong to your wife and your wife does not belong to you. But we do belong to each other because we have never felt this extraordinary thing called love, and that is our difficulty. We have committed ourselves in marriage, just as we have committed ourselves in learning a technique. Love is not commitment, but again that is a very difficult thing to understand, because the word is not the thing. To be sensitive to another, to have that pure feeling uncorrupted by the intellect, surely that is love. I do not know if you have considered the nature of the intellect. The intellect and its activities are all right at a certain level, but when the intellect interferes with that pure feeling, mediocrity sets in. To know the function of the intellect and to be aware of that pure feeling, without letting the two mingle and destroy each other, requires a very clear, sharp awareness.

Now, when we say that we must inquire into something, is there in fact any inquiring to be done, or is there only direct perception? Inquiry is generally a process of analysing and coming to a conclusion. That is the function of the mind, of the intellect. The intellect says, ‘I have analysed, and this is the conclusion I have come to.’ From that conclusion it moves to another conclusion, and so it keeps going. When thought springs from a conclusion, it is no longer thinking, because the mind has already concluded. There is thinking only when there is no conclusion. This again you will have to ponder over, neither accepting nor rejecting it. If I conclude that communism, Catholicism or some other “ism” is so, I have stopped thinking. If I conclude that there is God or that there is no God, I have ceased to inquire. Conclusion takes the form of belief. If I am to find out whether there is God, or what is the true function of the State in relation to the individual, I can never start from a conclusion, because the conclusion is a form of commitment. So the function of the intellect is always to inquire, to analyse, to search out. But because we want to be secure inwardly, psychologically, because we are afraid, anxious about life, we come to some form of conclusion to which we are committed. From one commitment we proceed to another, and I say that such a mind, such an intellect, being slave to a conclusion, has ceased to think, to inquire.

I do not know if you have observed what an enormous part the intellect plays in our life. The newspapers, the magazines, everything about us is cultivating reason. Not that I am against reason. On the contrary, one must have the capacity to reason very clearly, sharply. But if you observe you find that the intellect is everlastingly analysing why we belong or do not belong, why one must be an outsider to find reality, and so on. We have learnt the process of analysing ourselves. So there is the intellect with its capacity to inquire, to analyse, to reason and come to conclusions, and there is feeling, pure feeling, which is always being interrupted, coloured by the intellect. And when the intellect interferes with pure feeling, out of this interference grows a mediocre mind. On the one hand we have intellect, with its capacity to reason based upon its likes and dislikes, upon its conditioning, upon its experience and knowledge, and on the other we have feeling, which is corrupted by society, by fear. And will these two reveal what is true? Or is there only perception and nothing else?

A mind that is limited to reason and analysis is incapable of perceiving what is truth.

To me there is only perception, which is to see something as false or true immediately. This immediate perception of what is false and what is true is the essential factor, not the intellect with its reasoning based upon its cunning, its knowledge, its commitments. It must sometimes have happened to you that you have seen the truth of something immediately, such as the truth that you cannot belong to anything. That is perception: seeing the truth of something immediately, without analysis, without reasoning, without all the things that the intellect creates in order to postpone perception. It is entirely different from intuition, which is a word that we use with glibness and ease. And perception has nothing to do with experience. Experience tells you that you must belong to something otherwise you will be destroyed, you will lose your job, your family or property, or your position and prestige. So the intellect, with all its reasoning, with its cunning evaluations, with its conditioned thinking, says that you must belong to something, that you must commit yourself in order to survive. But if you perceive the truth that the individual must stand completely alone, then that very perception is a liberating factor; you do not have to struggle to be alone.

There is only this direct perception, not reasoning, not calculation, not analysis. You must have the capacity to analyse, you must have a good, sharp mind in order to reason, but a mind that is limited to reason and analysis is incapable of perceiving what is truth. To perceive immediately the truth that it is folly to belong to any religious organization, you must be able to look into your heart of hearts, to know it thoroughly, without all the obstructions created by the intellect. If you commune with yourself, you will know why you belong, why you have committed yourself, and if you push further you will see the slavery, the cutting down of freedom, the lack of human dignity which that commitment entails. When you perceive all this instantaneously you are free; you don’t have to make an effort to be free. That is why perception is essential. All efforts to be free come from self-contradiction. We make an effort because we are in a state of contradiction within ourselves; and this contradiction, this effort, breeds many avenues of escape which hold us everlastingly in the treadmill of slavery.

So it seems to me that one must be very serious, but I do not mean serious in the sense of being committed to something. People who are committed to something are not serious at all. They have given themselves over to something in order to achieve their own ends, in order to enhance their own position or prestige. The serious man is he who wants to find out what is freedom, and for this he must surely inquire into his own slavery. Don’t say you are not a slave. You belong to something, and that is slavery, though your leaders talk of freedom. So did Hitler or Khrushchev. Every tyrant, every guru, every president, everyone in the whole religious and political set-up talks of freedom. But freedom is something entirely different. It is a precious fruit without which you lose human dignity. It is love, without which you will never find God, or truth, or that nameless thing. Do what you will, cultivate all the virtues, sacrifice, slave, search out ways to serve man; without freedom none of these will bring to light that reality within your own heart. That reality, that immeasurable something, comes when there is freedom: the total inward freedom which exists only when you have not committed yourself, when you do not belong to anything, when you are able to stand completely alone without bitterness, without cynicism, without hope or disappointment. Only such a mind-heart is capable of receiving that which is immeasurable.

Krishnamurti in Madras 1959, Talk 1

Audio: Freedom, Space and Order

Freedom is the capacity to look at a psychological fact without distortion; and that freedom is at the beginning, not at the end. You must understand that time is a process of evasion and not a fact, except chronological time. But the psychological time that we have introduced, that of gradually bringing about a change in ourselves, has no validity. Because when you are angry, when you are ambitious, when you are envious, you take pleasure in it, you want it, and the idea that you will gradually change has no depth behind it at all. One removes psychological resistances by observing the fact and not allowing the mind to be caught in unreal, ideational, theoretical issues. When you are confronted with a fact there is no possibility of resistance; the fact is there. So freedom is to look at a fact without any idea, to look at a fact without thought.

Krishnamurti in New Delhi 1962, Talk 8