Until the 1980S, Krishnamurti, for the most part, used the words ‘brain’ and ’mind’ interchangeably. This article, presented in a chronological sequence, unfolds the differentiation between the mind and the brain, and inquires into the relationship between the two. It ends with an extract from Krishnamurti’s very last talk. A video option can be found below each of the Question & Answer extracts.

I mean by ‘mind’ the brain, the movement of thought, consciousness, the whole content of our consciousness, the senses – all that is the mind. I am using the word in that sense. We may alter it later on, use a different word, but for now we are using ‘mind’ to convey all that.

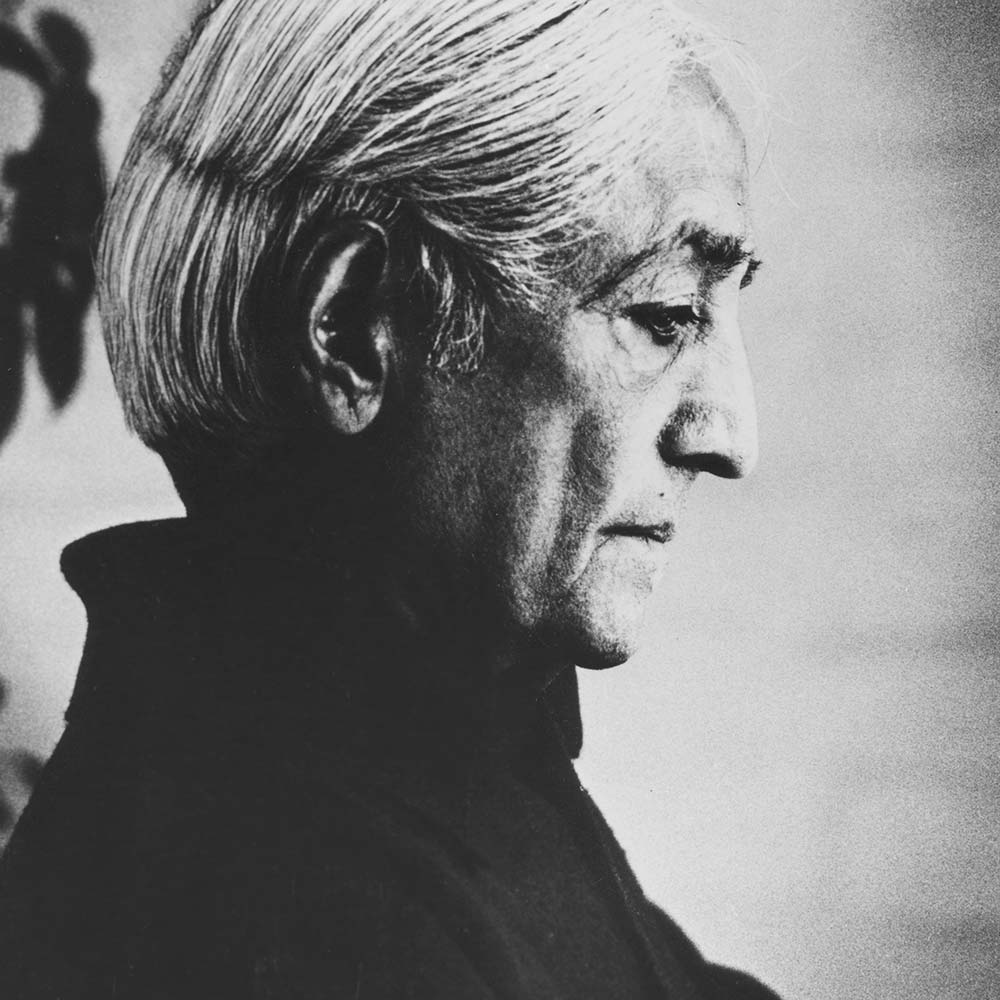

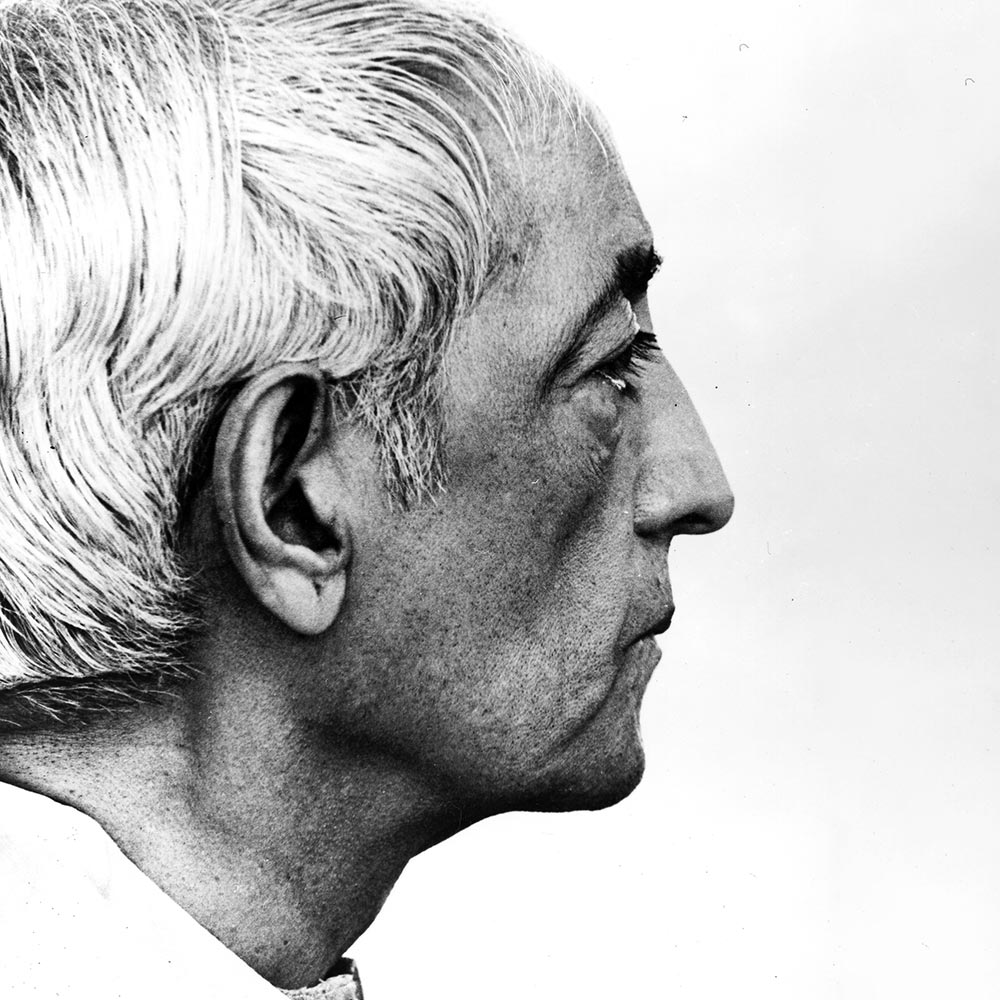

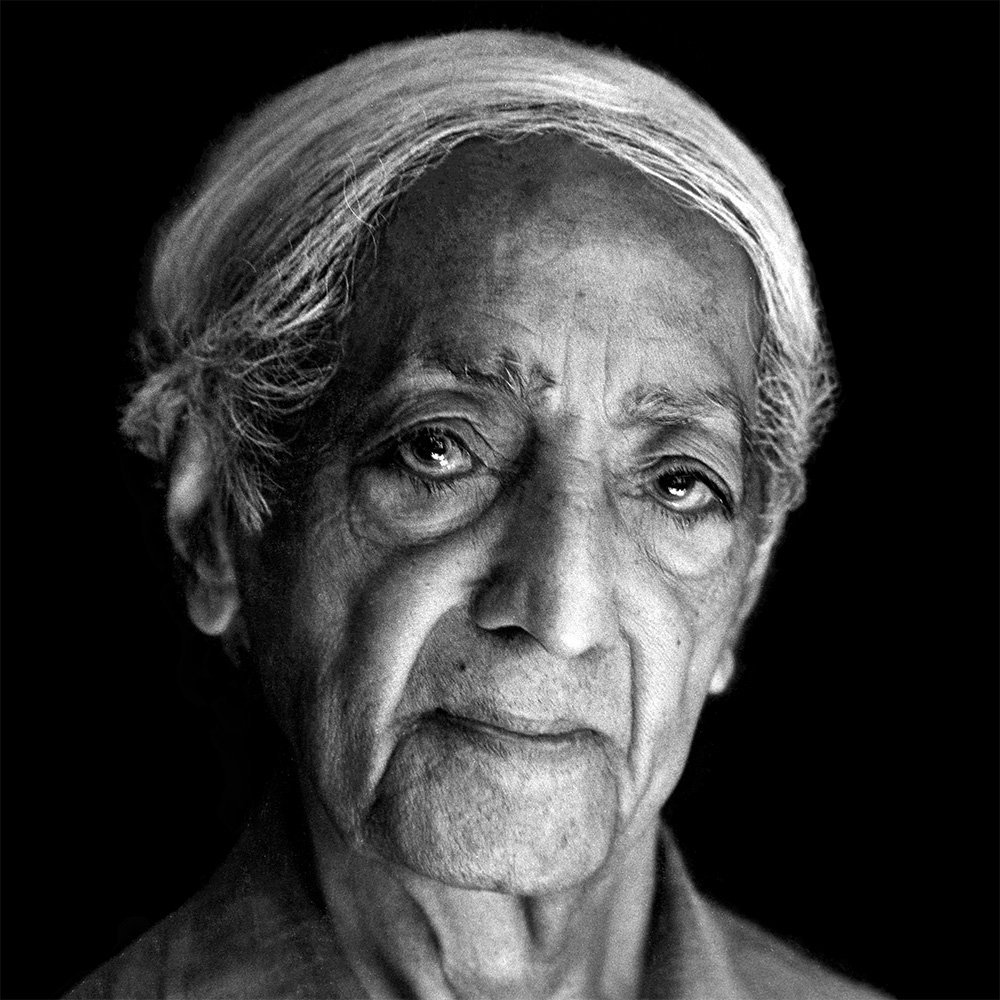

Krishnamurti in Saanen 1978, Talk 5

QuestioneR: You often switch over from using ‘mind’ to ‘brain’. Is there any difference between them? If so, what is the mind?

Krishnamurti: I am afraid it is a slip of the tongue. That is, I have often said ‘the mind, the brain’. I apologise for that; I was talking only about the brain.

The questioner wants to know what the mind is. Is the mind different from the brain? Is the mind something untouched by the brain? Is the mind not the result of time, which the brain is? Does this interest you? Let’s go into it.

First of all, to understand what the mind is, we must be very clear, as much as we can, about how our brain operates. Not according to the brain specialists or neurologists, those who have studied the brains of rats and pigeons in great detail, but we are studying, each one of us, if we are willing, the nature of our own brain: how we think, what we think, how we act, our behaviour, the immediate, spontaneous responses. Are we aware of all that? Are we aware that our thinking is in an extraordinarily narrow groove? Are we aware that our thinking is mechanical, in a certain particular trained activity, how our education has conditioned our thinking, how our careers, whether in an office, engineering or surgery, and so on, are all based on directional, conditioned knowledge? Are we aware of all this?

Tradition, when we accept it, makes the brain extraordinarily dull.

Scientists are now saying that thought is the expression of the brain’s memory – memory that gives rise to thought and action based on experience and knowledge. They are gradually coming to that, which we have been saying from the outset, that thought is a material process, there is nothing sacred about thought, and whatever it creates, whether mechanically or idealistically, or projects as a future in the hope of reaching some kind of happiness, peace, all of this is the movement of thought. Are we aware of this? When you go to a temple, it is nothing but a material process. You might not like to hear this, but that is the fact. Thought has created the architecture of the temple, the building, and the things inside it. The temple, the mosque and the church are all the result of thought. Are we aware of this and therefore moving in a totally different direction?

Tradition, when we accept it, makes the brain extraordinarily dull – it is just convenient repetition, and gradually the brain becomes stupid, routine, though you may be reading or talking endlessly about the Gita or scriptures. This is what happens when there is so much uncertainty in the world, so much pain, so much disorder and chaos – you turn to tradition. This is what is happening in the West and in the East, too, where they are becoming more and more fanatical. Are we aware of this? And can one stop all that, in oneself? Or are we so dull, so used to this confusion and misery that we put up with it?

We have to understand very clearly what the activity of the brain is, which means the activity of our consciousness, the psychological world in which we live. The whole of that – the brain, consciousness, the psychological world – all that is one. Would you question that? Probably you have not thought about all this. You read a great deal about these matters. If you are a psychologist or a psychoanalyst, if you are therapeutically inclined, you read a lot, but you don’t look at yourself, you don’t observe your own actions and behaviour. So that is why it is very important, if you would understand what the mind is, to understand how thought acts, since thought has created the content of our consciousness and the psychological world in which we live – the structure which thought has built in man: the ‘me’ and the ‘not me’, the ‘we’ and ‘they’, the quarrels, the battles in ourselves, between us as human beings.

Perhaps we can begin to see the nature of the mind.

The brain has evolved through time. That is obvious. It has evolved for millions of years, accumulating knowledge, experience and memory. It is the result of time; there is no doubt about that. But is love, compassion, with its intelligence, the product of thought? Are compassion and love the result of thought? Can you cultivate love? I am afraid that that feeling perhaps does not exist in our world. You read and talk about it – the scriptures talk about it sometimes, but the word is not the thing.

So that which is not of time, which is not the product of thought, which is not a material process, is the mind. Thought is in itself disorder, while mind is entire, absolute order, as the cosmos or universe. But to inquire, to go into that, realise that, you cannot understand the nature of the mind unless you have understood the nature of thought, all its activities deeply, and do so not just verbally but in yourself. Which means thought realises its place. Thought realises its place in technology, when you drive a car, when you speak a language, when you go to the office or factory, where skill needs thought to operate. And when thought realises its limitation and its place, then perhaps we can begin to see the nature of the mind.

Krishnamurti in Madras 1981, Q&A Meeting 1

Video: Is There Any Difference Between the Brain and Mind?

Questioner: You sometimes speak of the brain and also of the mind. Is there a difference between them? And if so, what is their relationship?

Krishnamurti: How would you answer this question? You are all, apparently, learning from me. Please don’t. Don’t please learn from another, especially in psychological and so-called spiritual matters. You have to be a light to yourself, and that light cannot be lit by another. The speaker is not teaching; we are observing our own brains, our own hearts, our own existence, our daily life as we live it.

The questioner asks what the difference is between the mind and the brain. What is the relationship between the two? Is there something separate as the mind apart from the brain? Or is there only the brain which has created the mind and then tries to establish a relationship between the two, a game it can play everlastingly? That is, the brain realises its limitation because it is conditioned, and is everlastingly in conflict. Thought is the instrument of the brain, so it invents a super-mind or super-consciousness and then tries to establish a relationship between the two. I don’t know if you see the game it plays.

Is there a mind apart from the brain?

So, we are asking whether there a mind apart from the brain that is not brought about by thought as a comforting idea. There is the brain that is conditioned, whose instrument is thought. Thought is brought about through sensations, experiences, knowledge and memory. That is the chain in which the brain lives. Knowledge can never be complete; knowledge must always go with ignorance – always. There is no complete knowledge of anything. So we realise this and project an idea of God as omnipotent and all the rest of it.

So is there a mind apart from the brain? Is the brain infinite? The brain is infinite if it is free from all conditioning. Am I merely spinning a lot of words, or are we following each other? As long as the brain is conditioned in any shape, or at any level, at any depth, it must be limited. When that limitation, restriction, confinement or conditioning is totally eliminated, when it disappears completely, the brain is infinite.

Q: I don’t quite follow that.

K: The capacity to perceive wholly, with holistic perception, is not possible if the brain is limited or prejudiced. Wait, let’s put it much more simply. If you are prejudiced, your thinking is always limited. This prejudice is the result of one’s conditioning. That conditioning limits the capacity of the brain. If I am a surgeon for the rest of my life, spending years specialising in medicine and surgery, my brain is limited; it cannot have a holistic perception. Even scientists who talk about holistic perception, if they are conditioned by fear, nationality, jealousy and all the rest of it, as most of them are, their brains are limited, and therefore they are incapable of holistic perception, though they may write about it. Holistic perception is possible only when there is the total elimination of conditioning. Man says that is not possible. Somebody comes along and says it is possible if you go carefully step by step and understand it very deeply.

So, the brain as it is now is limited by its conditioning, by its desire to be completely safe, secure in a relationship or a job. It feels it can function only when there is complete security. That is, if I am a first-class surgeon, and I am secure in that, the brain functions happily, but the brain is limited in its action. Is it possible to perceive something holistically apart from using the brain? This becomes a little more complex.

The brain as it is now is limited by its conditioning.

Have you ever perceived anything wholly? Please, investigate it a little bit. To perceive something wholly is not to let the word, image or symbol interfere with perception. Can we look at a tree, say, without calling it a tree? We can because the word ‘tree’ is not that. We have used the word ‘tree’ to symbolise or communicate a certain object. And so our brain is conditioned by words. So, can one be free of the word to look? That is fairly easy, to look at a tree without the word, but to look at ourselves without the word is much more complex because we live by words: I am an American, I am a Catholic – the word by itself means nothing, but thought has given content to that word.

So, to perceive something holistically is to perceive without time, that is, to have a global mind. Seeing humanity as a whole – not, I am identified with humanity, which is silly – but rather to see humanity with all its struggle, pain, anxiety, misery, joy, pleasure, the travail that human beings go through, as a human whole. I think that such holistic perception is part of the mind, is the mind. I won’t go into this more deeply, that is enough for the moment.

So the relationship between the mind and the brain can take place only when the brain is equally infinite, which is when it is free from its conditioning.

Krishnamurti in Ojai 1981, Q&A Meeting 1

Video: Is There a Difference Between the Brain and the Mind?

Krishnamurti: Are the psychologists really concerned with the future of humanity? Are they concerned with the human being conforming to the present society, or going beyond that?

DAVID BOHM: I think that most psychologists evidently want the human being to conform to this society, but I think some are thinking of going beyond that to transform the consciousness of mankind.

K: Can the consciousness of mankind be changed through time? That is one of the questions we should discuss.

DB: I think that what came out of our previous discussions was that with regard to consciousness, time is not relevant, that it is a kind of illusion. We discussed the illusion of becoming.

K: Yes, we are saying that the evolution of consciousness is a fallacy.

DB: As through time, yes. Though physical evolution is not.

K: Can we put it this way, much more simply? There is no psychological evolution or evolution of the psyche.

DB: Yes, and since the future of humanity depends on the psyche, it seems then that its future is not going to be determined through actions in time. And that leaves us with the question of what we will do.

K: Now let’s proceed from there. Shouldn’t we first distinguish between the brain and the mind?

DB: Well, that distinction has been made, but it is not clear. Of course, there are several views. One view is to say the mind is just a function of the brain – that is the materialist view. There is another view that the mind and brain are two different things.

K: Yes, I think they are two different things.

DB: But there must be…

K: …contact between the two. A relationship between the two.

DB: Yes, we don’t necessarily imply any separation of the two.

K: No. First, let’s see the brain. I am really not an expert on the structure of the brain and all that kind of thing. But one can see within one, observe from the activity of one’s own brain, that it is really like a computer that has been programmed and remembers.

DB: Well, certainly a large part of its activity is that way, but one is not certain that all of it is that way.

K: No. And it is conditioned. Conditioned by past generations, by society, by the media, by all the activities and pressures from the outside. It is conditioned.

DB: Yes. Now, what do you mean by this conditioning?

K: The brain is programmed. It is made to conform to a certain pattern. It lives entirely on the past, modifying itself with the present, and going on.

DB: We have agreed that some of this conditioning is useful and necessary.

K: Of course.

DB: But the conditioning which determines the self, the psyche, that is the conditioning you are talking about. That may not only be unnecessary but harmful.

K: Yes. The emphasis on the psyche, giving importance to the self, is causing great damage in the world, because it is separative. Therefore it is constantly in conflict not only within itself, but also with society, with the family, and so on.

DB: Yes. And it is also in conflict with nature.

K: With nature, with the whole universe.

DB: We have said that the conflict arose because of division arising because thought is limited. Being based on this conditioning, knowledge and memory, it is limited.

K: Yes. And experience is limited. Therefore knowledge, memory and thought are limited. Thought is limited, and the very structure and nature of the psyche is the movement of thought.

DB: Yes.

K: In time.

The brain is programmed. It is made to conform to a certain pattern.

DB: Yes. Now, I would like to ask a question. You have referred to the movement of thought, but it doesn’t seem clear to me what is moving. You see, if I talk of the movement of my hand, that is a real movement. It is clear what is meant. But when we now discuss the movement of thought, it seems we are discussing something that is a kind of illusion, because you have said becoming is the movement of thought.

K: That is what I meant, the movement in becoming.

DB: But what you are saying is that in some way that movement is illusory, aren’t you?

K: Yes, of course.

DB: It is rather like the movement on the screen projected from the camera. We say there are no objects moving across the screen, that the only real movement is the turning of the projector. Now, can we say there is a real movement in the brain which is projecting all this, which is the conditioning?

K: That is what we want to find out. Let’s discuss that a bit. We both agree, or see, that the brain is conditioned.

DB: Really what we mean by that is that it has been impressed physically and chemically.

K: And genetically, as well as psychologically.

DB: What is the difference between physically and psychologically?

K: Psychologically, the brain is centred in the self, right?

DB: Yes.

K: And the constant assertion of the self is its movement, conditioning, an illusion.

DB: But there is some real movement happening inside. The brain, for example, is doing something. It has been conditioned physically and chemically. And something is happening physically and chemically when we are thinking of the self.

K: Are you asking whether the brain and the self are two different things?

DB: No, I am saying that the self is the result of conditioning the brain.

K: Yes. And the self is conditioning the brain.

DB: But does the self exist?

K: No.

DB: But the conditioning of the brain, as I see it, is its involvement with an illusion which we call the self.

K: That’s right. Can that conditioning be dissipated? That’s the question.

DB: It really has to be dissipated in some physical, chemical and neurophysiological sense.

K: Yes.

DB: Now, the first reaction of any scientific person would be that it looks unlikely that we could dissipate it by the sort of thing we are doing. Some scientists might feel that maybe we will discover drugs or new genetic changes or deep knowledge of the structure of the brain. In that way, we could perhaps hope to do something. I think that idea might be current among some people.

K: Will that change human behaviour?

DB: Well, why not? I think some people believe it might.

K: Wait a minute. That is the whole point. It might, which means in the future.

DB: Yes, it would take time to discover all this.

K: In the meantime, man is destroying himself.

DB: Well, they might hope that he will manage to do it in time. They could also criticise what we are doing here, asking what good it can do. You see, it doesn’t seem to affect anybody, and certainly not in time to make a big difference.

K: We two are very clear about it. In what way does it affect humanity?

DB: Will it really affect mankind in time to save…

K: Certainly not. Obviously not.

DB: Then why should we be doing it?

K: Because this is the right thing to do. Independently. It has nothing to do with reward and punishment.

DB: Nor with goals. You do the right thing even though we don’t know what the outcome will be?

K: That’s right.

DB: Are you saying there is no other way?

K: We are saying that there is no other way, that’s right.

DB: We should make that clear. For example, some psychologists would feel that by inquiring into this sort of thing, we could bring about an evolutionary transformation of consciousness.

K: We come back to the point that through time we hope to change consciousness. We question that.

DB: We have questioned that and are saying that through time we are all caught inevitably in becoming and illusion, and we will not know what we are doing.

K: That’s right.

DB: Now, could we say the same thing would hold even for those scientists who are trying to do it physically, chemically or structurally, that they are still caught in this, and through time they are caught in trying to become better?

K: Yes, the experimentalists and the psychologists are trying to become something.

DB: Yes, though it may not seem obvious at first. It may seem that they are just disinterested scientists, unbiased observers working on the problem. But underneath you feel there is the desire to become better on the part of the person who is inquiring in that way.

K: To become, of course.

DB: They are not free of that.

K: That is just it.

DB: And that desire will give rise to self-deception and illusion, and so on.

K: So where are we now? Any form of becoming is an illusion, and becoming implies time for the psyche to change. But we are saying time is not necessary.

DB: Yes, that ties up with the other question of the mind and the brain. The brain is clearly activity in time, as a complex physical and chemical process.

K: I think the mind is separate from the brain.

DB: What does it mean, separate? Are they in contact?

K: Separate in the sense that the brain is conditioned and the mind is not.

DB: Well, let’s say the mind has a certain independence of the brain. Even if the brain is conditioned…

K: …the other is not.

DB: It need not be conditioned. Now, what makes you say that?

K: As long as the brain is conditioned, it is not free. And the mind is free.

DB: Yes, that is what you are saying. The brain not being free means it is not free to inquire in an unbiased way.

So as long as the brain is conditioned, its relationship to the mind is limited.

K: I will go into it. Let’s inquire. What is freedom? Freedom to inquire, as you point out, freedom to investigate. It is only in freedom there is deep insight.

DB: Yes, that’s clear, because if you are not free to inquire, or if you are biased, then you are limited, in an arbitrary way.

K: So as long as the brain is conditioned, its relationship to the mind is limited.

DB: Yes, now we have the relationship of the brain to the mind, and also the other way round.

K: The mind being free has a relationship to the brain.

DB: We are saying the mind is free, in some sense, that it is not subject to the conditioning of the brain.

K: Yes.

DB: Now, what is the nature of the mind? Is the mind located inside the body, or is it in the brain?

K: No, it is nothing to do with the body or the brain.

DB: Has it to do with space or time?

K: Space. Now, wait a minute! It has to do with space and silence. These are the two factors of the…

DB: But not time, right?

K: Not time. Time belongs to the brain.

DB: You say space and silence. Now, what kind of space? It is not the space in which we see life moving.

K: No, space. Let’s look at it around the other way. Thought can invent space.

DB: We have the space that we see and, in addition, thought can invent all kinds of space.

K: Space from here to there.

DB: Yes, the space through which we move physically.

K: Space also between two sounds.

DB: Space between two sounds is called the interval.

K: Yes, the interval between two sounds, two notes, two thoughts.

DB: Yes.

K: Space between two people.

DB: Space between walls.

K: And so on. But that kind of space is not the space of the mind.

DB: You are saying that it is not limited?

K: That’s right. But I didn’t want to use the word ‘limited’.

DB: But it is implied. That kind of space is not in the nature of being bounded by something.

K: No, it is not bounded by the psyche.

DB: But is it bounded by anything?

K: No. So can the brain, with all its cells conditioned, can those cells radically change?

DB: It is not certain that all the cells are conditioned. Some people think that only a small percentage of the cells are being used and the others are inactive, dormant.

K: Hardly used at all, or just touched occasionally.

DB: Just touched occasionally. But those cells that are conditioned, evidently dominate consciousness now.

K: Yes, can those cells be changed? We are saying that they can, through insight. Insight being out of time, and not the result of remembrance, intuition, desire or hope. It is nothing to do with time and thought.

DB: Yes. Now, is insight of the mind? Is it of the nature of mind, an activity of mind?

K: Yes.

DB: Therefore you are saying mind can act in the matter of the brain.

K: Yes.

DB: This point, how mind is able to act in matter, is a difficult one.

K: It is able to act on the brain. For instance, take any crisis or problem. The root meaning of ‘problem’ is something thrown at you. And we meet it with the remembrance of the past, with a bias, and so on. Therefore the problem multiplies itself. You may solve one problem, but in the very solution of that particular problem, other problems arise, as happens in politics and so on. Now, to approach the problem, or to have perception of it without past memories and thoughts interfering or projecting…

DB: That implies perception also is of the mind.

K: Yes, that’s right.

DB: Are you saying that the brain is a kind of instrument of the mind?

K: An instrument of the mind when the brain is not self-centred.

DB: Yes, all the conditioning may be thought of as the brain exciting itself and keeping itself going just from that program. This occupies all its capacities.

K: All our days, yes.

The brain is operating in a very, very small area.

DB: The brain is rather like a radio receiver which can generate its own noise but would not pick up a signal.

K: Not quite. Let’s go into this a little bit. Experience is always limited, right? I may blow up that experience into something fantastic and then set up shop to sell my experience, but that experience is limited. Knowledge is always limited, and this knowledge is operating in the brain. This knowledge is the brain. And thought is also part of the brain, and thought is limited. So the brain is operating in a very, very small area.

DB: Yes. What prevents it from operating in a broader area? In an unlimited area?

K: Thought.

DB: Thought. But the brain, it seems to me, is running on its own, from its own program.

K: Yes, like a computer.

DB: Now, essentially, what you are asking is that the brain should really be responding to the mind.

K: It can only respond if it is free from the limited – from thought, which is limited.

DB: Yes, so the program then does not dominate it. We are still going to need that program.

K: Of course. We need it for…

DB: …for many things. Yes.

Is intelligence from the mind?

K: Yes. Intelligence is the mind.

DB: Is the mind.

K: We must go into something else because compassion is related to intelligence. There is no intelligence without compassion. And compassion can only be when there is love, which is completely free from all remembrances, jealousies and all that kind of thing.

DB: Are compassion and love also of the mind?

K: Of the mind. You see, you cannot be compassionate if you are attached to any experience or ideal.

DB: Yes, that is again the program that is holding us.

K: Yes. For instance, people go to poverty-ridden countries and work, work, work. And they call that compassion. But they are attached or tied to a particular form of religious belief, and therefore that is merely pity or sympathy. It is not compassion.

DB: Yes, I understand that we have here two things which can be somewhat independent. There is the brain and the mind, though they make contact. Now we are saying that intelligence and compassion come from beyond the brain. So now I would like to go into the question of how they are making contact.

K: Contact can only exist between the mind and the brain when the brain is quiet.

DB: Yes, that is the condition, the requirement for making it. The brain has got to be quiet.

K: And that quiet is not a trained quietness. It is not a self-conscious, meditative desire for silence. It is a natural outcome of understanding one’s conditioning.

DB: And if the brain is quiet, you could say it can listen to something deeper, right?

K: Deeper – that’s right. Then if it is quiet, it is related to the mind. Then the mind can function through the brain.

DB: Now, I think it would help if we could see with regard to the brain, whether it has any activity which is beyond thought. For example, one could ask if awareness is part of the function of the brain.

K: As long as it is awareness in which there is no choice – not I am aware, and in that awareness I choose.

DB: I think that may cause difficulty. What is wrong with choice?

K: Choice means confusion.

DB: That is not obvious just from the word itself.

K: Of course, you have to choose between two things.

DB: I could choose whether I will buy one thing or another.

K: Yes, I can choose between this table and that table.

DB: I choose the colour when I buy the table. That need not be confused.

K: There is nothing wrong, no confusion there.

DB: But it seems that choice with regard to the psyche is where the confusion is.

K: That is all we are talking about – the psyche that chooses.

DB: That chooses to become.

K: Yes, chooses to become. And choice also exists where there is confusion.

Contact can only exist between the mind and the brain when the brain is quiet.

DB: Are you saying that out of confusion, the psyche makes a choice to become one thing or another? Being confused, it tries to become something better?

K: And choice implies a duality.

DB: Yes, but now it seems, at first sight, you have introduced another duality: the mind and the brain.

K: No, that is not a duality.

DB: That is important to get clear. What is the difference?

K: Let’s take a very simple example. Human beings are violent, and non-violence has been projected by thought. That is duality – the fact and the non-fact.

DB: You are saying there is a duality between a fact and some mere projection the mind makes.

K: The ideal and the fact.

DB: The ideal is unreal, and the fact is real.

K: That’s it. The ideal is not actual.

DB: Yes. Now, you are saying the division of those two is duality. Why do you give it that name?

K: Because they are divided.

DB: Well, at least they appear to be divided.

K: Divided, and we are struggling with that. For instance, the totalitarian communist ideals and democratic ideals are the outcome of thought, which is limited. And this is creating havoc in the world.

DB: So there is a division which has been brought in. But I think we were discussing in terms of dividing something which cannot be divided, of trying to divide the psyche.

K: That’s right. Violence cannot be divided into non-violence.

DB: Yes. And the psyche cannot be divided into violence and non-violence.

K: It is what it is.

DB: It is what it is. So if it is violent, it cannot be divided into violent and non-violent parts.

K: That’s right. So can we remain with what is, not with what should be, what must be and not invent ideals and all the rest of that?

DB: Yes, but could we return to the question of the mind and the brain? We are saying that is not a division.

K: Oh no, that is not a division.

DB: They are in contact.

K: We said there is contact between the mind and the brain when the brain is silent and has space.

DB: Yes, so we are saying that although they are in contact and not divided at all, the mind can still have a certain independence of the conditioning of the brain.

K: Let’s be very careful here. Suppose my brain is conditioned, for example, programmed as a Hindu, and my life and actions are conditioned by the idea that I am a Hindu. Mind obviously has no relationship with that conditioning.

DB: You are using the word ‘mind’, not ‘my mind’.

K: Mind – it is not mine.

DB: It is universal or general.

K: Yes. And it is not my brain either.

DB: No, but there is a particular brain, this brain or that brain. Would you say there is a particular mind?

K: No.

DB: Now, that is an important difference. You are saying mind is universal.

K: Mind is universal – if you can use that ugly word.

DB: Unlimited and undivided.

K: It is unpolluted, not polluted by thought.

DB: For most people, there will be difficulty in saying how we know anything about this mind. I only know of my mind, is the first feeling.

K: You cannot call it your mind. You only have your brain, which is conditioned. You cannot say, ‘It is my mind.’

DB: Yes, but whatever is going on inside I feel is mine, and is very different from what is going on inside somebody else.

K: No, I question whether it is different.

DB: At least it seems different.

K: Yes. I question whether it is different, that which is going on inside me as a human being and you as another human being. We both go through problems, suffering, fear, anxiety, loneliness, and so on. We have our dogmas, beliefs and superstitions. And everybody has this.

DB: Well, we say it is all very similar, but it still seems as if each one of us is isolated from the other.

K: By thought. My thought has created the belief that I am different from you because my body is different from yours and my face is different from yours. We extend that difference into the psychological area.

DB: So now we are saying that division is perhaps an illusion.

K: No, not perhaps – it is.

DB: All right, it is an illusion. Although it is not obvious when one first looks at it.

K: Of course.

DB: In reality, even the brain is not divided, because we are saying that we are all not only basically similar but really connected. And then we say beyond all that is mind, which has no division at all.

K: It is unconditioned.

DB: Yes, it would seem to imply that insofar as a person feels they are a separate being, they have very little contact with mind.

K: Absolutely. Quite right.

DB: No mind.

Mind is universal.

K: That is why it is very important to understand not the mind but my conditioning. And then whether my conditioning, human conditioning, can ever be dissolved. That is the real issue.

DB: Yes. I still want to understand the meaning of what is being said. We have a mind that is universal; that is in some kind of space, you say. Or is it its own space?

K: It is not in me or in my brain.

DB: But it has a space.

K: It lives in space and silence.

DB: It lives in a space and silence, but it is the space of the mind. It is not a space like this space.

K: No. That is why we said a space that is not invented by thought.

DB: Yes. Is it possible then to perceive this space when the brain is silent, to be in contact with it?

K: Not perceive. Let’s see. You are asking whether the mind can be perceived by the brain.

DB: Or at least the brain somehow be aware… an awareness, a sense of it.

K: We are saying yes. Through meditation. You may not like to use that word.

DB: I don’t mind.

K: You see, the difficulty is that when we use the word ‘meditation’, it is generally understood to mean that there is a meditator meditating. Meditation is really an unconscious process, not a conscious process.

DB: But how can you say meditation takes place if it is unconscious?

K: It is taking place when the brain is quiet.

DB: Well, you mean by consciousness all the movement of thought? Feeling, desire, will and all that goes with it?

K: Yes.

DB: But there is still a kind of awareness, isn’t there?

K: Oh yes. It depends what you call awareness. Awareness of what?

DB: I don’t know. Possibly awareness of something deeper.

K: You see, again, when you use the word ‘deeper’ it is a measurement. I wouldn’t use that.

DB: Well, let’s not use that. But there is a kind of unconsciousness which we are simply not aware of at all. A person may be unconscious of some of his problems or conflicts.

K: Let’s go at it a bit more. If I do something consciously, it is the activity of thought.

DB: Yes, it is thought reflecting on itself.

K: Right, it is the activity of thought. Now, if one consciously meditates, practises, does all that – which I call nonsense – one is making the brain conform to another series of patterns.

DB: Yes, it is more becoming.

K: More becoming – that’s right.

DB: You are trying to become better.

K: There is no illumination by becoming.

DB: But it seems very difficult to communicate something which is not conscious.

K: That’s it. That’s the difficulty. Let’s put it this way. Conscious meditation, conscious activity to control thought, to free oneself from conditioning, is not freedom.

DB: Yes, I think that is clear, but it becomes very unclear how to communicate something else.

K: Wait a minute. Say you want to tell me what lies beyond thought.

DB: Or when thought is silent.

K: Quiet, silent – what words would you use?

DB: I suggested the word ‘awareness’. What about ‘attention’?

K: Attention for me is better. Would you say that in attention there is no centre as the ‘me’?

DB: Well, not in the kind of attention to which you are referring. There is the usual kind, where we pay attention because of what interests us.

K: Attention is not concentration.

DB: No, we are discussing a kind of attention without the ‘me’ being present, and which is not the activity of conditioning.

K: Not the activity of thought. In attention, thought has no place.

DB: Yes, but could we say more? What do you mean by attention? Would the derivation of the word be of any use? It means stretching the mind. Would that help?

K: No. Would it help if we say effort and concentration are not attention? When I make an effort to attend, it is not attention. Attention can come into being only when the self is not.

DB: Yes, but that is going to get us in a circle because we are starting when the self is.

K: No, let’s go back to the word ‘meditation.’ As long as there is measurement, which is becoming, there is no meditation. Let’s put it that way.

DB: Yes. We can discuss that which is not meditation.

K: That’s right. Through negation, the other is.

DB: Because if we succeed in negating the whole activity of what meditation is not, meditation will be there.

K: Yes, that’s right. That is very clear. As long as there is measurement, which is becoming, which is the process of thought, meditation or silence cannot be.

DB: Is this undirected attention of the mind?

K: Attention is of the mind.

DB: And it contacts the brain?

K: Yes. As long as the brain is silent, the other has contact.

DB: This true attention has contact with the brain when the brain is silent.

K: Silent, and has space.

DB: What is this space?

K: The brain has no space now because it is concerned with itself. It is programmed; it is self-centred and limited.

DB: Yes. The mind is in its space, and you are saying that the brain also has its space? Limited space.

K: Of course. Thought has limited space.

DB: But when thought is absent, does the brain have its space?

K: Yes. The brain has space.

DB: Unlimited?

K: No. It is mind only that has unlimited space. My brain can be quiet over a problem which I have thought about, and I suddenly say, ‘I won’t think any more about it,’ and there is a certain amount of space. In that space, you solve the problem.

DB: Yes, if the brain is silent, is not thinking of a problem, then the space is still limited, but it is open to…

K: …to the other.

It is mind only that has unlimited space.

DB: To the attention. Would you say that through attention or in attention, the mind is contacting the brain?

K: Yes, when the brain is not inattentive.

DB: So, what happens to the brain?

K: What happens to the brain? Which is to act. Wait, let’s get it clear. We said intelligence is born out of compassion and love. That intelligence operates when the brain is quiet.

DB: Yes. Does it operate through attention?

K: Of course, of course.

DB: So attention seems to be the contact.

K: Naturally. We have also said that attention can be only when the self is not.

DB: Yes. Now, you say love and compassion are of the ground, and out of this comes intelligence through attention.

K: Yes, through attention, intelligence functions through the brain.

DB: So let’s say there are two questions. What is the nature of this intelligence? And the second is, what does it do to the brain?

K: Yes, let’s see. That is, we must again approach it negatively. Love is not jealousy. Love is not personal, but it can be personal.

DB: Then it is not what you are talking about.

K: Yes. Love is not my country or your country, or ‘I love my God.’ It is not that.

DB: Well, if it is from universal mind…

K: That is why I say love has no relationship to thought.

DB: Yes, and it does not start or originate in a particular brain.

K: Yes, it is not my love. When there is love, out of it there is compassion and intelligence.

DB: Is this intelligence able to understand deeply?

K: No, not understand.

DB: What does it do? Does it perceive?

K: Through perception, it acts.

DB: Yes, but perception of what?

K: Now, let’s discuss perception. There can be perception only when it is not tinged by thought. When there is no interference from the movement of thought, there is perception, which is direct insight into a problem or into human complexity.

DB: Yes. Now, this perception originates in the mind?

K: Does the perception originate in the mind? Let’s look at it. Yes. When the brain is quiet.

DB: We have used the words ‘perception’ and ‘intelligence’. How are they related, or what is their difference?

K: The difference between perception and intelligence?

DB: Yes.

K: None.

DB: So we are saying intelligence is perception.

K: Yes, that’s right.

DB: Intelligence is perception of what is, right? And through attention, there is contact.

K: Let’s take a problem and look at it, then it will probably be easier to understand. Take the problem of suffering. Human beings have suffered endlessly, through wars, through every kind of disease, and through wrong relationship with each other. Now, can that end?

DB: I would say the difficulty of ending it is that it is of the program. We are conditioned to this whole thing, physically and chemically.

K: Yes, and that has been going on for centuries.

DB: Yes, so it is very deep.

K: Very, very deep. Now, can that suffering end?

DB: It cannot end by an action of the brain.

K: By thought.

DB: Because the brain is caught in suffering and it cannot take action to end its own suffering.

K: Of course it cannot. Thought has created it, and that is why thought cannot end it.

DB: Yes, thought has created it, and anyway it is unable to get hold of it.

K: Thought has created wars, misery and confusion. Thought has become prominent in human relationship.

DB: Yes. I think people might agree with that, but still think just as thought can do bad things, it can do good things.

K: No, it is thought, limited.

DB: Thought cannot get hold of this suffering. That is, this suffering being in the physical and chemical conditioning of the brain, thought has no way of even knowing what it is. I don’t know, by thinking, what is going on inside me. I can’t change the suffering inside because thinking will not show me what it is. Now, you are saying intelligence and perception do.

K: We are asking whether suffering can end. That is a problem.

DB: Yes, and it is clear that thinking cannot end it.

K: Thought cannot do it. That is the point. If I have an insight into it…

DB: Yes. Now, this insight will be through the action of the mind, through intelligence, and attention.

K: When there is that insight, intelligence wipes away suffering.

DB: You are saying, therefore, that there is a contact from mind to matter which removes the whole physical and chemical structure that keeps us suffering.

K: That’s right. In that ending, there is a mutation in the brain cells.

DB: Yes, and that mutation wipes out the whole structure that makes you suffer.

K: Yes. It is as if I have been going along in a certain tradition: I suddenly change that tradition, and there is a change in the whole brain. I had been going north; now it goes east.

Intelligence operates when the brain is quiet.

DB: This is a radical notion from the point of view of traditional ideas in science because if we accept that mind is different from matter, people will find it hard to say mind would actually…

K: Mind, after all, is… would you put it that mind is pure energy?

DB: Well, we could put it that way, but matter is energy too.

K: But matter is limited. Thought is limited.

DB: Yes, but are we saying that the pure energy of mind is able to reach into the limited energy of matter?

K: Yes, that’s right. And change the limitation.

DB: Yes, to remove some of the limitation.

K: When there is a deep issue, problem or challenge which you are facing.

DB: We could also add that all the traditional ways of trying to do this cannot work because…

K: They have not worked.

DB: Well, that is not enough – we have to say why, because people might still hope it could, but actually it cannot.

K: It cannot.

DB: Because thought cannot get at its own physical and chemical basis in the cells, and do anything about those cells.

K: Yes, we have said that very clearly. Thought cannot bring about a change in itself.

DB: And yet practically everything that mankind has been trying to do is based on thought. There is a limited area where that is all right, but we cannot do anything about the future of man from that usual approach.

K: When one listens to the politicians, who are so very active in the world and create problem after problem, to them thought and ideals are the most important things.

DB: Well, generally speaking, nobody knows of anything else.

K: Exactly. We are saying that the old instrument, which is thought, is worn out, except in certain areas.

DB: And it was never adequate except in those areas. As far back as history goes, man has always been in trouble.

K: Man has always been in trouble, in turmoil, in fear. We must not reduce all this to an intellectual argument. But as human beings, facing all the confusion of the world, can there be a solution to all this?

DB: That comes back to the question I would like to repeat. It seems there are a few people who are talking about it, and think perhaps they know, perhaps meditate, and so on, but how is that going to affect this vast current of mankind?

K: Probably very little. But will it affect that? It might or it might not. But then one puts the question: What is the use of it?

DB: Yes, that is the point. I think there is an instinctive feeling that makes one put that question.

K: Yes, but I think that is a wrong question.

DB: You see, the first instinct is to say, ‘What can we do to stop this tremendous catastrophe?’

K: Yes. But if each one of us, whoever listens, sees the truth that thought in its activity externally and inwardly has created a terrible mess, great suffering, then one must inevitably ask if there is an ending to all this. If thought cannot end it, what will? What is the new instrument that will put an end to this misery? There is a new instrument, which is the mind, which is intelligence. But the difficulty is that people won’t listen to all this. The scientists and laypeople have come to definite conclusions, and they won’t listen.

DB: Yes. Well, that is what I had in mind when I said that a few people don’t seem to have much effect.

K: Of course. Though I think a few people, whether good or bad, have changed the world. Hitler did.

DB: He didn’t change it fundamentally.

K: No, he changed the world superficially, if you like. The revolution of the communists changed it, but they have gone back to the same old pattern. Physical revolution has never changed the human psychological state.

DB: Do you think a certain number of brains coming in contact with mind in this way will be able to have an effect on mankind, which is beyond just the immediate obvious effect of their communication?

K: Yes, that’s right. That’s right.

DB: I mean, obviously whoever does this may communicate in the ordinary way, and it will have a small effect, but there is a possibility of something entirely different.

K: How do you – I have often thought about this – how do you convey this rather subtle and very complex issue someone who is steeped in tradition, who is conditioned and won’t even take time to listen and consider?

DB: Yes, that is the question. You could say this conditioning cannot be absolute, cannot be an absolute block, or else there would be no way out at all. The conditioning may be thought to have some sort of permeability. Is it possible that every person has something they can listen to if it could be found?

K: If one has a little patience. Perhaps it is like a wave in the world that might catch somebody. I think it is a wrong question to ask whether it affects mankind.

DB: Yes. That brings in time, and that is becoming. It again brings about in the psyche the process of becoming.

K: Yes. But if you say… It must affect mankind.

DB: Well, are you proposing that it affects mankind through the mind directly, rather than through…

K: Yes. It may not show immediately in action.

DB: You are taking very seriously what you said, that the mind is universal and is not located in our ordinary space.

K: Yes, but there is a danger in saying that the mind is universal. That is what some people say of the mind, and it has become a tradition.

DB: You can turn it into an idea, of course.

K: That is the danger of it.

DB: Yes. Really the question is to come directly in contact with this to make it real.

K: That’s it. We can only come into contact with it when the self is not. To put it very simply: when the self is not, there is beauty, silence, space. Then that intelligence which is born of compassion operates through the brain. It is very simple.

DB: Yes. Would it be worth discussing the self, since the self is so widely active?

K: That is our long tradition of many, many centuries.

DB: Is there some aspect of meditation which can be helpful here when the self is acting? Suppose a person says, ‘I am caught in the self, but I want to get out.’

The observer is the observed. And when there is that actuality, you have eliminated conflict altogether.

K: That is very simple. Is the observer different from the observed?

DB: Well, suppose we say it appears to be different – then what?

K: Is that an idea or an actuality?

DB: What do you mean?

K: Actuality is when there is no division between the thinker and the thought.

DB: Yes, but suppose I say ordinarily one feels the observer is different from the observed. Say we begin there.

K: We will begin there. I’ll show you. Look at it. Are you different from your anger, envy and suffering? You are not.

DB: At first sight, it appears that I am, that I might try to control it.

K: Not control it; you are that.

DB: Yes, but how will I see that I am that?

K: You are your name. You are your form, body. You are all the reactions and actions. You are the belief, fear, suffering and pleasure. You are all that.

DB: Yes, but the first experience is that I am here first and that those are properties of me. They are qualities which I can either have or not have. I might be angry or not angry; I might have this belief or that belief.

K: Yes, contradictory. You are all that.

DB: But it is not obvious. When you say I am that, do you mean that I am that and cannot be otherwise?

K: No. At present, you are that. It can be totally otherwise.

DB: All right. So I am all that. Rather than saying, as I usually do, that I am looking at those qualities, and feel that I am not angry but an unbiased observer looking at anger, you are telling me that this unbiased observer is the same as the anger at which he is looking.

K: Of course. Just as I analyse myself and the analyser is the analysed.

DB: Yes. He is biased by what he analyses.

K: Yes.

DB: So if I watch anger for a while, I can see that I am very biased by the anger. So at some stage, I say I am one with that anger?

K: No, not ‘I am one with it’ – I am it.

DB: Anger and I are the same.

K: Yes. The observer is the observed. And when there is that actuality, you have eliminated conflict altogether. Conflict exists when I am separate from my quality.

DB: Yes, that is because if I believe myself to be separate, I can try to change it. But since I am that, it is not trying to change itself and remain itself at the same time, right?

K: Yes, that’s right. When the quality is me, the division has ended.

DB: Yes, when I see that the quality is me, there is no point in trying to change it.

K: What happened before, when the quality is not me, is conflict, suppression, escape, and so on, which is a waste of energy. When that quality is me, all that energy which had been wasted is there to look, observe.

DB: But why does it make such a difference to have that quality being me?

K: It makes a difference when there is no division between the quality and me.

DB: Yes, well, when there is no perception of a difference…

K: That’s right. Put it that way.

DB: …then the mind does not try to fight itself.

K: Yes, yes. It is so.

DB: If there is an illusion of a difference, the brain is compelled to fight against itself.

K: Yes, that’s right.

DB: On the other hand, when there is no illusion of a difference, the brain just stops fighting.

K: And therefore you have tremendous energy.

DB: So the brain’s natural energy is released?

K: Yes. And energy means attention.

DB: Yes. Well, the energy of the brain allows for attention…

K: …for that thing to dissolve.

DB: Yes, but wait a minute. We said before that attention was a contact of the mind and the brain.

K: Yes.

DB: So the brain must be in a state of high energy to allow that contact.

K: That’s right.

DB: A brain which is low energy cannot allow that contact.

K: Of course not. Most of us are low energy because we are so conditioned.

DB: Essentially, you are saying that this is the way to start.

K: Yes, start simply. Start with what is, what I am. Self-knowledge is so important. It is not an accumulative process of knowledge, which then looks; it is a constant learning about oneself.

DB: Yes, if you call it self-knowledge, then it is not knowledge of the kind we talked about before, which is conditioning.

K: That’s right. Knowledge conditions.

DB: You are saying self-knowledge of this kind is not conditioning. But why do you call it knowledge? Is it a different kind of knowledge?

K: Self-knowledge, which is to know and to comprehend, to understand oneself – oneself is such a subtle, complex, living thing.

DB: Essentially knowing yourself in the very moment in which things are happening.

K: Yes, to know what is happening.

DB: Rather than store it up in memory.

K: Of course. And through reactions, I begin to discover what I am.

The Ending of Time

To inquire, to have further insight, to observe if there is something beyond thought, not put together by it, thought must end completely. The very necessity to find out ends thought. Say I want to climb a mountain. I have to train, I have to work, day after day climbing more and more. I have to put my energy into that. So the necessity to find out if there is something more than thought, that very necessity creates the energy which then ends thought. The importance of ending thought in order to observe further, that very importance brings about the ending of thought. It is as simple as that. Don’t complicate it.

Thought, which is limited, has its own space, its own order. When the activity of thought ceases, there is space. Not only in the brain, but space. Not the space that the self creates around itself, but limitless space. When thought discovers for itself its limitation and sees that it is creating havoc in the world, that very observation brings thought to an end, because you want to discover something new. An engineer who knows all about the internal combustion engine, who has worked with it for years and says, ‘I want to discover something more than that,’ they have to put all that aside to see something new. If they carry all that with them all the time, they can’t see anything new. That is how the jet engine was discovered. The man who discovered it completely understood internal combustion, the piston, the propeller and all that, and said there must be something more. He was watching, waiting, listening. And he came upon something new.

Similarly, one sees that thought is limited. And whatever it does, it will always be limited. Because by its very nature it is conditioned and therefore limited, the machinery of thought cannot go beyond itself. So one says, ‘If I have the urge to go further, that machinery must come to a stop.’ Then the ending of thought begins. Then there is space and silence. Meditation is understanding the meaning of measurement, and of the ending of psychological measurement, which is becoming – the ending of that, and also seeing that thought is everlastingly limited. It may think of the limitless, but it is born of limitation. So it comes to an end. Then the brain, which has been chattering along, muddled, limited, suddenly becomes silent, without any compulsion or discipline, because it sees the fact and truth of its limitation. That fact and truth are beyond time. And so thought comes to an end.

Then there is that sense of absolute silence in the brain. All the movement of thought has ended. It has ended, but can be brought into activity when it is needed in the physical world. But now it is quiet, silent. Where there is silence, there must be space, immense space, because there is no self from which – you get it? The self has its own limited space. When you are thinking about yourself, it creates its own little space. But when the self is not, which means that the activity of thought ceases, there is vast silence in the brain, because it is now free from all its conditioning. And where there is space and silence, only then something new can be, untouched by time and thought. That may be the most holy, the most sacred – may be. You cannot give it a name. It is perhaps the unnameable. And when there is that, there is intelligence, compassion and love. Life then is not fragmented; it is a whole, unitary, moving, living process.

Krishnamurti in Saanen 1983, Talk 6

Questioner: Could we speak about the brain and the mind? Thinking takes place materially in the brain cells. If thinking stops and there is perception without thought, what happens in the material brain? You seem to say the mind has its place outside the brain, but where does the movement of pure perception take place if not some-where in the brain? And how is it possible for a mutation to take place in the brain cells if pure perception has no connection in the brain?

Krishnamurti: Have you understood the question? It is a good question, so please listen to it. I am listening to it too.

First, the questioner wants to differentiate, separate, distinguish between the mind and the brain. Then they ask if pure perception is outside the brain – which means thought is not the movement of perception. And they ask: If perception takes place outside the brain – which is the thinking and remembering process – then what happens to the brain cells themselves that are conditioned by the past? And will there be a mutation in the brain cells if perception is outside? Is this clear? Are you sure?

So let’s begin with the brain and the mind. The brain is a material function. It is a muscle, like the heart. The brain cells contain memories. Please, I am not a brain specialist, nor have I studied the experts, but I have lived a long time now, and I have watched a great deal, not only the reaction of others – what they say, what they think, what they want to tell me – but also I have watched how the brain reacts. I won’t go into what my brain is, that is unimportant. I know you would like that! (Laughter)

The brain has extraordinary capacity.

The brain has evolved through time: from the single cell, taking millions and millions of years, until it reached the ape, and went on another million years until ultimately the human brain. The brain is contained within the skull, but it can go beyond itself. You can sit here and think of your home, and you are instantly there in thought. The brain has extraordinary capacity. See what it has done technologically, the extraordinary things they are doing.

So the brain has extraordinary capacity. That brain has been conditioned by the limitation of language, the climate it lives in, the food it eats, the social environment, the society in which it lives. That society has been created by the brain, so that society is not different from the activities of the brain. And there are thousands of years of experience, thousands of years of accumulated knowledge based on that experience, which is tradition. I am British, you are German; he is a Hindu, he is a black man, he is this, he is that – all the nationalistic divisions, which is tribal division, and the religious conditioning. So the brain is conditioned. Being conditioned, it is limited. The brain has extraordinary capacity, but it has been conditioned and therefore is limited. It is not limited technologically, but it is very, very limited with regard to the psyche. The ancient Greeks, the Hindus and others have said ‘know yourself’, and the psychologists, philosophers and experts study the psyche in others but they never study their own psyche, they never study themselves. They study rats, rabbits, pigeons, monkeys and so on, but they don’t say, ‘I am going to look at myself. I am ambitious, greedy, envious; I compete with my neighbour and my fellow scientists, I want a better this or that.’ This is the same psyche that has existed for thousands of years. Man is marvellous technologically, externally, but inwardly very primitive.

One has to have an extraordinarily subtle brain to see where the self is hiding.

So the brain is limited and primitive in the world of the psyche. Can that limitation be broken down? Can that limitation, which is the self, the ego, the ‘me’, the self-centred concern, can all that be wiped away? Which means the brain is then unconditioned. Then it has no fear. Most of us live in fear. Most of us are anxious, frightened of what is going to happen, frightened of death, anxious about a dozen things. Can all that be completely wiped away and be fresh so that the brain is free? Then its relationship to the mind is entirely different.

I must say here that we have discussed this with several scientists, and they won’t go as far as the speaker has gone. They go along with it theoretically, but not actually. See the difference. That is, to see that one has no shadow of the self. To see that the ‘me’ does not enter into any field is extraordinarily arduous. The self hides in many ways, under every stone. The self can hide in compassion – going to India to look after the poor because the self is attached to some idea, faith, conclusion or belief which makes me compassionate because I love Jesus or Krishna and I will go to heaven. The self has many, many masks: the mask of meditation, the mask of achieving the highest, the mask that I am enlightened. This concern about humanity is another mask. So one has to have an extraordinarily subtle brain to see where the self is hiding. It requires great attention, watching, watching, watching. You won’t do all this – probably you are too lazy or too old, and you say, ‘For God’s sake, all this is not worth it. Leave me alone.’ But if one really wants to go into this very deeply, one has to watch like a hawk every movement of thought, every movement of reaction, so the brain can be free from its conditioning.

The speaker is speaking for himself, not for anybody else. He may be deceiving himself. He may be trying to pretend to be something or other. He may be, you don’t know. So have a great deal of scepticism, doubt. Question – not asking what others say but go into all this yourself.

The mind is pure energy and intelligence.

When there is no conditioning of the brain, it no longer degenerates. As we get older, our brains generally begin to wear out. We lose our memory and behave peculiarly. Degeneration takes place in the brain. When the brain is completely free of the self and is therefore no longer conditioned, then we can ask what the mind is.

We have talked to some of the so-called learned people in India. They are learned but only about what other people have said. The ancient Hindus inquired into the mind, and they have posited various statements. But wiping all that out, not depending on somebody however ancient, however traditional, what is the mind? We live in disorder. Our brain functions in disorder. Our brain is constantly in conflict. Therefore it is in disorder. Such a brain cannot understand what the mind is. The mind, not my mind but the mind that has created the universe and the cell, is pure energy and intelligence – you don’t have to believe this – and that mind, when the brain is free, can have a relationship to the brain. But if the brain is conditioned, it has no relationship. Intelligence is the essence of the mind. Not the intelligence of thought or disorder. The mind is pure order, pure intelligence, and therefore it is pure compassion. That mind has a relationship with the brain when the brain is free.

The questioner says, ‘You say the mind is outside the brain, the mind is not contained in the brain.’ We have discussed this with scientists, and they say yes – perhaps casually to please me, or theoretically they see, but the speaker is talking factually for himself. The questioner asks how perception, which takes place only when there is no activity of thought, can bring about a mutation in the brain cells, which are a material process. Keep it very simple. That is one of our difficulties: we don’t look at a complex thing very simply. Here is a very complex question, and we must begin very simply to understand something very vast.

When there is perception, there is a mutation in the brain cells.

Traditionally you have pursued a certain path – religiously, economically, socially, morally, and so on – a certain direction all your life. Suppose I have done this and you come along and say the way I am going leads nowhere. It will bring you much more trouble; you will everlastingly kill each other, you will have tremendous economic difficulties – you give me logical reasons, examples and so on. But I say, ‘No, sorry, this is my way of doing things,’ and I keep going that way. Most people do. Ninety-nine per cent of people keep going that way, including the gurus, philosophers and the newly-achieved enlightened people. But you say, ‘That is a dangerous path, don’t go there. Turn and go in another direction entirely.’ And you convince me, show me the logic, the reason, the sanity of it, and I turn and go in a totally different direction.

What has taken place? I have been going in one direction all my life, and I move in another direction. What has happened to the brain? Keep it simple. Going in one direction and suddenly moving in the other direction, the brain cells themselves have changed. I have broken the tradition. It is as simple as that. But the tradition is strong. It has its roots in my present existence, and you are asking me to do something against which I rebel. Therefore I do not listen. But if I listen to find out if what you are saying is true or false, to know the truth of the matter, not my wishes or pleasures, but wanting to know the truth of it, I therefore, being serious, listen with all my being, and I see you are quite right. I have moved. In that movement, there is a change in the brain cells.

We have been brought up to live with fear. You tell me it can end, and instinctively I want to find out if what you are saying is true or false, whether fear can really end. So I spend time to discuss with you. I want to learn, so my brain is active to find out, not to be told what to do. The moment I begin to inquire, work, look, watch the whole movement of fear, either I accept it, or I move away from it. When I see that, there is a change in the brain cells. It is so simple if you could only look at this thing very simply. When there is perception, there is a mutation in the brain cells, not through any effort, not through will or any motive. Perception is when there is observation without a movement of thought, which is time and memory – to look at something without the past. Do it. Look at the speaker without all the remembrance that you have accumulated about him. Watch him. Watch your father or mother, husband, wife or friend, without any past remembrance, hurt or guilt. Just watch. When you so watch without any prejudice, there is freedom from that which has been.

Krishnamurti in Saanen 1983, Q&A Meeting 2

Video: Could We Speak About the Brain and the Mind?

Questioner: What is the difference between the brain and the mind?

Krishnamurti: This is a very complex question. The brain contains the whole content of consciousness. Consciousness is your belief, faith, name, faculty, capacity, memories, hurts, pleasures, pain, agony, sorrow, affection, and so on. All that is the content of your consciousness. The content of your consciousness is you, the self, the ‘me’. That content of consciousness may invent a super-consciousness or imagine various states, but it is still within the content of your consciousness. You are your name, your body, your anger, greed, competitiveness, ambition, pleasure, pain – you are that, and that is the content of your consciousness. The content of your consciousness is the past – memories, incidents, activities, experiences. You are the past. You are knowledge, which is the past. So, that is the brain.

We are saying – and the speaker may be wrong, so please don’t accept what he says, but doubt, question, inquire. He says the brain is the whole limited consciousness, with all its content, pleasant, unpleasant, ugly, beautiful. And the mind is something totally separate from the brain. The mind is outside the brain. The speaker is saying this, not the scientists. The speaker says the brain is one thing and mind is something entirely different. The brain, with all its content, with its struggles, pain and anxieties, can never know or understand the beauty of love. Love is limitless. It is not that you love one person only – love is too vast, too tremendous. And the brain with all its content, miseries and confusion, cannot comprehend, hold or be alive to love; only the mind, which is limitless.

The intelligence of thought cannot contain the intelligence of the mind.

So there is a difference between the brain and the mind. The questioner does not ask about the relationship between the mind and the brain. The brain is limited, because it is made up of all kinds of separate parts, is fragmented, broken up, and therefore it is in a constant state of struggle and conflict, whereas the mind is totally out of that category. There is a relationship only when the brain is completely free, if that is possible, from all the content of its memories. This requires a great deal of inquiry and sensitivity. Intelligence is not of the brain. The intelligence of thought cannot contain the intelligence of the mind.

Be very simple, because if you can be very, very simple, you can go very, very far. But if you begin with lots of complex theories and conclusions, you get stuck. So let’s be simple. In your daily life, going to the office, working, working, working, trained in a certain discipline, a lawyer, surgeon, businessman, cook, or whatever it is, your brain is being narrowed down, limited. If I am a physicist, I spend years learning about physics, studying, investigating, doing research, so my brain is being narrowed down. Our brains have become mechanical, routine, small, because we are so concerned with ourselves, always living in a very, very small area of like and dislike, pain and sorrow. But the mind is something entirely different. You cannot understand or comprehend the nature of that mind if your brain is limited. You cannot understand the limitless when your life is limited. So, relationship between the brain and the mind can take place only when the brain is free from its content. This is a complex question; it requires much more going into.

Krishnamurti in Bombay 1984, Q&A Meeting

Video: What Is the Difference Between the Brain and the Mind?

What is religion? What is the religious mind? What is the mind? We must differentiate between the brain and the mind. The brain is the storehouse of memories, the seat of action and reaction, of response both neurologically and psychologically, contained as consciousness in the brain. Psychologically, subjectively, we are very limited. So the brain is limited, though as we can see, technologically it has infinite capacity. That is all part of the brain. The mind is something entirely different. The mind is outside the brain.

Love too is not within the brain. It is outside. If it is within the brain, it is a process of thought, memory, recollection, remembrance, pleasure and pain, which means the brain contains that consciousness. Our consciousness is its content. There is no consciousness, as we know it, without its content. The content is our pain, loneliness, beliefs, faith, hopes, aspirations, anxieties – all that is our consciousness, contained within the skull. Love is surely not that. Love is not a battleground, reaction or a remembrance. When there are reaction and remembrance, it is of the brain. So were love part of the brain, it would be a reaction, and that is obviously not love.

We are going to investigate together into what religion is. Why has man spent such energy, inquired so much, suffered, fasted, tortured himself to find truth and that which is timeless? Every religion has done this. That is, religions say to find that which is immense, immeasurable, you must do certain things: control, discipline, dedicate your life to that, and only then will you find it. They put it more complicatedly, but that is what religions have said. In Christianity, as in Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam, there is a figure, a symbol; the mysteries in a not too well-lit place, in cathedrals and churches, with all the rituals, accepting and obeying – all that is called religion.

Is that religion, or is religion something entirely different? We have intermediaries, the priests, between the highest and the so-called lowest. Priests act as interpreters, like the psychiatrists, and they have played a great part since the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians and so on. The priests were the learned people and established laws and rules. I hope you are sceptical, doubting, questioning, not accepting anything, not psychologically obeying without going into it, not belonging to any sect, guru or organised religion. We are heavily conditioned by thousands of years of propaganda, programmed. If you can put all that aside, as one must if one wants to find that which is nameless, then what is religion? What is the quality of a brain that has totally set aside all man’s past endeavour, all his systems, methods, systems of meditation, breathing correctly, sitting cross-legged? Those are all meaningless. Calming the brain, breathing properly, quietly sitting in silence, will not bring about that which is immense. So what is the quality of a brain that has set aside all this? It is untrammelled; it has no bondage; it is completely free. The word ‘freedom’ has its etymological root in love – freedom means love.

See for yourself the extraordinary quality of the brain.

So, is that possible when the world is shouting, and being entertained by religions? Is it possible to live in this world daily with such total freedom from all tradition and knowledge, except where knowledge is necessary? We are asking a very difficult question because knowledge prevents true perception. So from that arises the question of what meditation is. Not how to meditate. The word ‘meditation’ has been brought over by gurus. They have their systems, practices and disciplines, and get a lot of money out of it. There are Hindu meditations, Tibetan meditations, various schools of meditation, Zen, the whole lot of them. What are they offering? What is meditation? Not how to meditate, or what system to follow – that is too immature – but the deep questions are what it means to meditate and why one should meditate.

The word ‘meditation’, etymologically and in Sanskrit, means to measure, to ponder over, to think over. Measurement means comparison. The speaker is saying that where there is comparison, there is no meditation. We are always measuring: the better, the more, the less, the greater. Can this movement of measurement, which is comparison, end completely, both psychologically and outwardly? That is part of meditation. Meditation means not only to ponder over, look and observe, but also the complete ending of all comparison, which is a pattern of the self. Where there is measurement, there is self. So is it possible to live a daily life without comparison? Then you will see for yourself the extraordinary quality of the brain. Then the brain itself has its own movement and another quality, being extraordinarily stable, firm. That does not mean it cannot yield, but it yields in firmness, in strength. Meditation also means freedom from the network of words and thought, so that the brain is not entangled with words, patterns, systems and measurement. Then there is absolute silence. And that silence is necessary.

Silence has its own sound. Have you ever listened to a tree? This is not a crazy question. Have you ever listened to an old tree when the breeze has come to an end and the tree is utterly silent, not a leaf fluttering? Then you listen to the sound of the tree; you find out the sound in silence, and there is a complete, absolute, not relative, silence. Relative silence can be brought about through thought and will, saying, ‘I must be silent.’ That is not silence at all. There is silence only when there is freedom from all the things man has accumulated. In that silence, there is an enormous sense of vastness and immensity. You don’t ask questions any more. It is.