Can we know and understand the full meaning of death? That is, can the mind be completely nothing, with no residue of the past? Whether that is possible or not is something we can inquire into, search out diligently, vigorously, work hard to find out. But if the mind merely clings to what it calls living, which is suffering, this whole process of accumulation, and tries to avoid the other, then it knows neither life nor death. So the problem is to free the mind from the known, from all the things it has gathered, acquired, experienced, so that it is made innocent and can therefore understand that which is death, the unknowable.

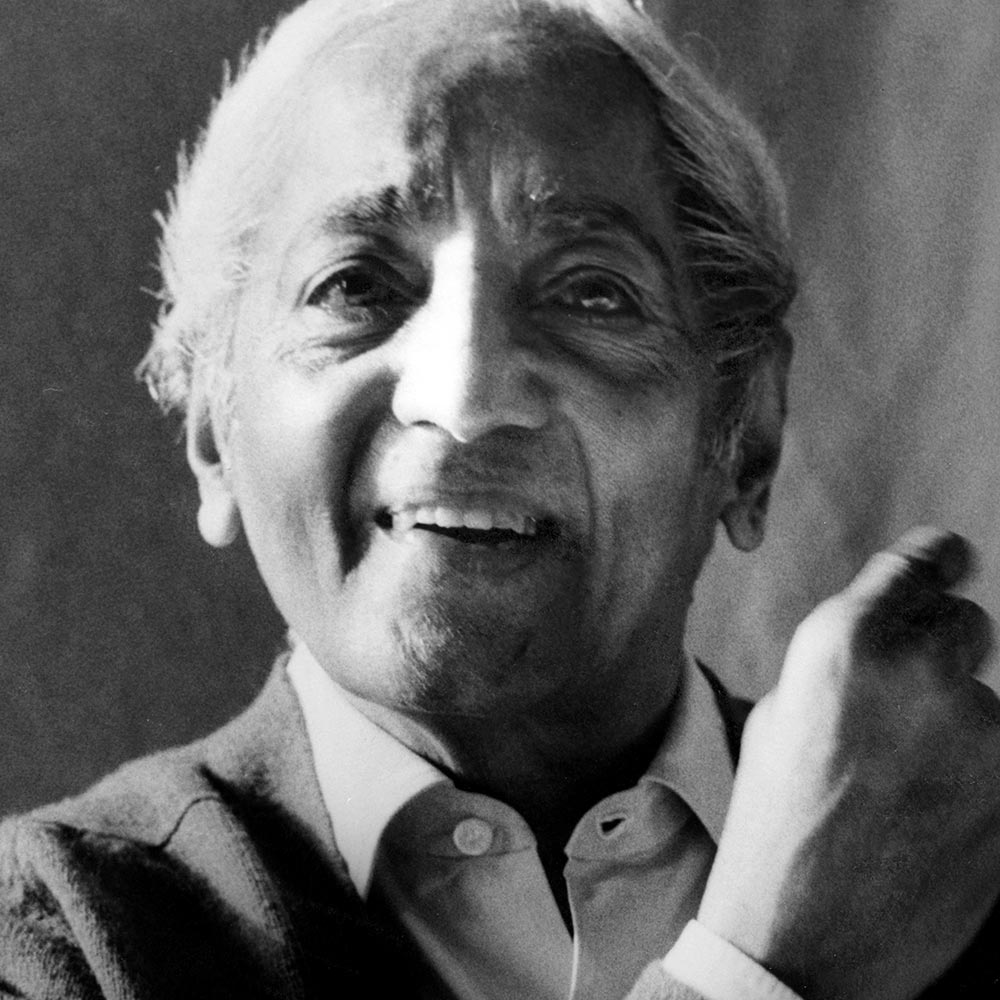

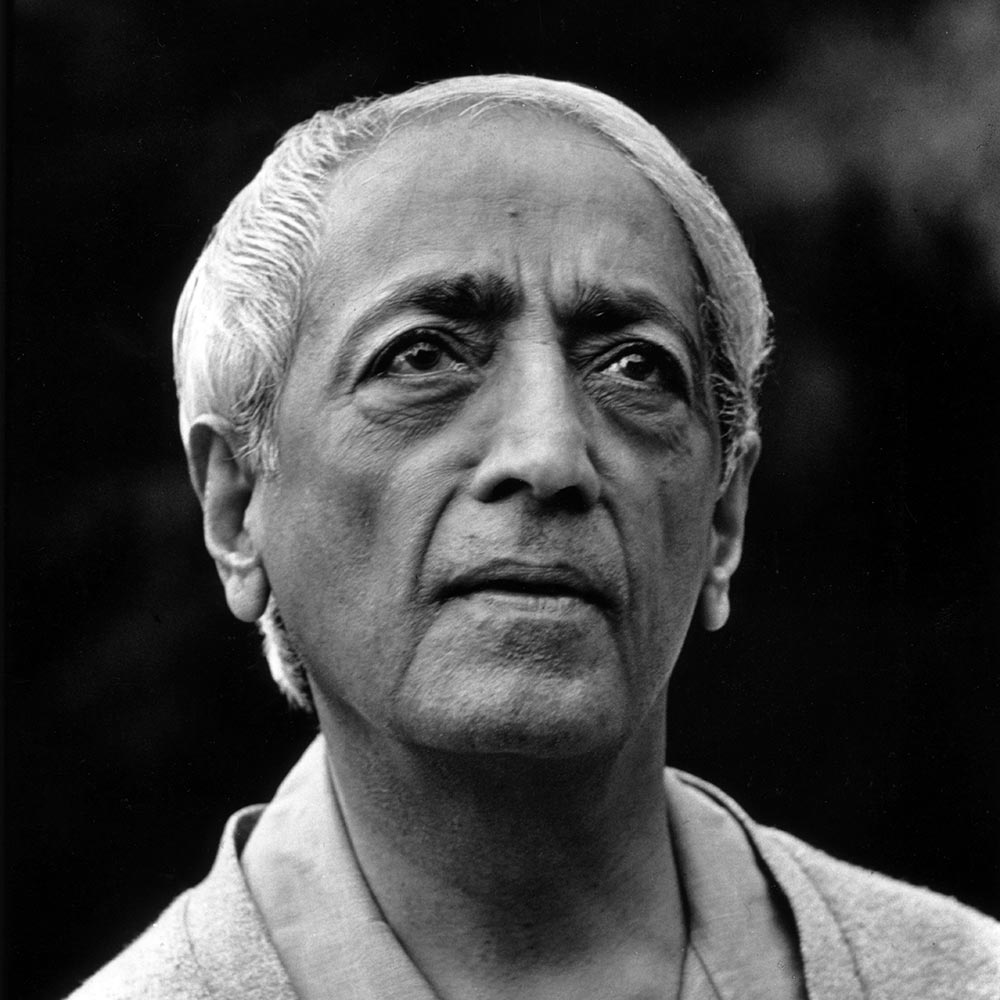

Krishnamurti in Brussels 1956, Talk 5

Living With Death

To find out what is death there must be no distance between death and you who are living with your troubles and all the rest of it; you must understand the significance of death and live with it while you are fairly alert, not completely dead, not quite dead yet. That thing called death is the end of everything that you know. Your body, your mind, your work, your ambitions, the things that you have built up, the things that you want to do, the things that you have not finished, the things that you have been trying to finish – there is an end of all these when death comes. That is the fact: the end. What happens afterwards is quite another matter; that is not important because you will not inquire what happens afterwards if there is no fear. Then death becomes something extraordinary, not sadistically, not abnormally or unhealthily, because death then is something unknown, and there is immense beauty in that which is unknown. These are not just words.

We are talking about dying to the things that your mind clings to.

So to find out the whole significance of death, what it means, to see the immensity of it, not just the stupid, symbolic image of death, this fear of living and the fear of dying must completely cease, not only consciously but also deep down. Our lives being empty we try to give significance to life, meaning to life. We ask, ‘What is the purpose of living?’ because our own lives are shallow, worthless and we think we must have an ideal to live by. It is all nonsense. So fear is the origin of the separation between that fact which you call death and that fact which you call living. What does death mean actually, not theoretically? We are not discussing theoretically, we are not discussing merely to formulate an idea, a concept. We are talking of facts, and if you reduce a fact merely into a theory, it is your own misfortune. You will live with your own shadow of fear and your life will end miserably as it has begun miserably.

So you have to find out how to live with death. Not a method; you cannot have a method to live with something you don’t know. You cannot have that idea and say, ‘Tell me the method and I will practise it and I will live with death.’ That has no meaning. You have to find out what it means to live with something that must be an astonishing thing, actually to see it, actually to feel it – to be aware of this thing called death and of which you are so terribly frightened. What does it mean to live with something which you don’t know? I don’t know if you have ever thought about it at all in that way; probably you have not. All that you have done is, being frightened of it you try to avoid it, you do not look at it. Or you jump to some hopeful ideal or belief and thereby avoid it. But you have really to find out what death means, and whether you can live with it as you would live with your wife or husband, with your children, your job, your anxiety. You live with all these, don’t you? You live with your boredom, your fears. Can you live in the same way with something that you don’t know?

To find out what it means to live, not only with the thing called life but also with death, which is the unknown, to go into it very deeply, we must die to the things that we know. I am talking about psychological knowledge, not of things like your home or office. We are talking about dying to the things that your mind clings to. You know, we want to die to the things which give us pain; we want to die to the insults, but we cling to the flattery. We want to die to the pain but we hold on like grim death to the pleasure. Please observe your own mind. Can you die to that pleasure, not eventually but now? You do not reason with death, you cannot have a prolonged argument with death. You have to die voluntarily to your pleasure, which does not mean that you become harsh, brutal, ugly, like one of the saints – on the contrary, you become highly sensitive; sensitive to beauty, to dirt, to squalor; and being sensitive, you care infinitely.

Life and death are not divided; they are one.

Now, is it possible to die to that which you know about yourself? To die – I am taking a very superficial example – to a habit, to put away a particular habit either of drinking or smoking, having a particular kind of food, or the habit of sex, completely to withdraw from it without an effort, without a struggle, without a conflict. Then you will see that you have left behind the knowledge, the experience, the memories of all the things that you have known and learnt and lived by. And therefore you are no longer afraid, and your mind is astonishingly clear to observe what this extraordinary phenomenon is, of which man has been frightened through millennia, to observe something which you are confronted with, which is of no time, and which in its entirety is the unknown. Only that mind can so observe, which is not afraid and which is therefore free from the known – the known of your anger, your ambitions, your greeds, your petty little pursuits. All these are the known. You have to die to them, to let them go voluntarily, to drop them easily, without any conflict. And it is possible; this is not a theory. Then the mind is rejuvenated, young, innocent, fresh; and therefore it can live with that thing called death. Then you will see that life has an entirely different substance. Then life and death are not divided; they are one, because you are dying every minute of the day in order to live. And you must die every day to live, otherwise you merely carry along the repetition like a gramophone record, repeating, repeating, repeating.

So when you really have the perfume of this thing, in your breath, in your being; not on some rare occasions but every day, waking and sleeping, then you will see for yourself, without somebody telling you, what an extraordinary thing it is to live, with actuality, not with words and symbols, to live with death and therefore to live every minute in a world in which there is not the known, but there is always the freedom from the known. It is only such a mind that can see what is truth, what is beauty and that which is from the everlasting to the everlasting.

Krishnamurti in New Delhi 1963, Talk 5

Video: Love, Life and Death Are Indivisible

Are Life and Death Two Separate Things?

Krishnamurti: What does death mean to you? Have you ever considered the question or do you postpone that dreadful event and carry on, knowing all around you there is death? When you see the victims of the recent wars in the Far East, that appalling suffering, misery, destroying marvellous trees, and a poor child not knowing what it is all about, crying on the roadside, when you look at all that, what is death? You must have considered it. For most of us does death mean the ending of life? Is that what we are frightened about? And what is our daily life to which we cling to so enormously? May I ask you, have you thought about it at all, have you inquired into it, have you made research into this enormous problem which has confronted man from the beginning of time? What does it mean to you?

Questioner: Death is the ending of the body.

K: Not only the ending of the body – what does death mean to you? Do you know what death means?

Q: Death is the ending of what we are.

K: Sir, you see somebody die, put in a coffin, a lot of flowers, put in a hearse and taken to the cemetery. Have you ever looked at it, observed it? What does it mean, that man or woman in a coffin? Don’t you react to it? Don’t you ask, ‘What does it all mean? What does living mean? What does dying mean?’ You see death: your friend, your son, your brother, uncle. What does it mean to you, somebody dying, a man killed so brutally and uselessly in Vietnam? And what is living? What is life? Don’t you ask?

There is a battle between the living, the known, and death the unknown.

Let’s begin. What does living mean to you? The actual daily living: the office, the factory, the quarrels, ambitions, the everlasting struggle in relationship, the brutality, violence, the hopes, distractions, pleasures, fears – all that is living, what is actually going on – earning a livelihood, the intellectual reasoning, technology, the immense progress science has made, and my daily living of sorrow, endless conflict, with occasional joy and pleasure, vast memories, remembrance of things that are gone – all that is my life, isn’t it? One always lives in the field of the known, in the field of the past. That’s our life: frustration, desire to be identified with something, struggle, conflict, having no love and wanting to be loved, loneliness, the expression of technological knowledge, your relationship with your wife or husband, the immense fears, the things that are hidden, which you read about in books and try to identify from the book what is happening to yourself. Isn’t that all your life?

Q: Life is time, and death perhaps is going out of time.

K: I don’t know, that is your idea. We are going to find out. Your life, and the life of human beings throughout the world, is a constant struggle, to earn a livelihood, to stay alive, disease, pain, trying to be moral, trying to behave properly or rejecting behaviour and trying to do something totally different, worship this god or that god, or be an atheist, communist or socialist – that is our life, the whole field of it. And we cling to that because that is the only thing we know. So the mind avoids death because it doesn’t know what is going to happen; basically it says, ‘I know the living.’ However troublesome, however painful, however pleasurable, however agonising, destructive, that is all I know and I hold on to that. I don’t know the other. I can speculate, I can invent, I can rationalise, I can have marvellous beliefs about it, but the fact is I cling to the known. So the mind is always seeking security in relationship, in something permanent. The mind is always demanding it and that security is within the field of the known, the known being knowledge, experience, memory.

So one can say living is a great travail, with occasional flashes of something else, and death is the unknown. And so there is a battle between the living, the known, and death the unknown. The ancient Egyptians and others tried to carry over their furniture, ivory, beautiful masks, lovely jewellery slaves and paintings into the other world they believed in. In Asia they say there is a permanent entity as the “me”, the soul, that will through righteous behaviour in the present improve itself in the future life. So they believe in reincarnation. By that they mean a better life. And though they believe that, it is all just words because their behaviour in daily life is just ordinary, brutal, envious. So the belief doesn’t matter a hoot. What matters is their enjoyment or their pleasures in the field of the known. When you observe all this, from the ancient times to the present day, those who believe in the resurrection and those who believe in reincarnation, those who only worship the present, they are always living in the known. Let’s begin with that. What is it that is known, to which we cling? I cling to my life. What for?

Q: Because I am afraid of emptiness.

K: Do you know what that means or is that just words? Are you clinging to that? Why does the mind cling to the known and avoid that thing which is called death? Why does the mind cling to this?

Q: I think I enjoy my life.

K: Is that the only thing you have, just enjoying your life and therefore you cling to it?

Q: I realise there is also pain.

K: You realise there is pain, there is frustration, there is everything including enjoyment, and you cling to that. What makes the mind cling to something which is so transient? I might have pleasure today, and out of that pleasure the pain comes tomorrow, and I know this enjoyment is so fleeting yet I cling to it – why?

Q: It is the only thing I know.

K: Why does the mind cling to something that is so transient?

Q: It is the only thing we have got.

K: What have you got? Examine it. What is it you have got? All the trouble of old age, disease, pain? Why does the mind, your mind, cling to something that you call the known, with all the pain and fury inside that? Is it because the known gives it security?

Q: It gives us life.

K: So you call life this battle, this process – is that it? If in death you found something permanent, secure, you would love that too, wouldn’t you? So the mind wants security: however fleeting, however painful, however destructive, violent or enjoyable. In that there is some security, some sense of survival, some sense of knowing. The known gives to the mind a sense of safety, so the mind clings to it.

Can you know death in the same way as you know living?

Can you know death in the same way as you know living, to which you cling? I know what living is, I have lived it for thirty, forty, eighty years. I know the content of it, the beauty of the hills and meadows, the movement of the leaves, the tranquil seas, I have known all that, seen it. I know it, I have felt it, I have lived it, I have suffered, I have been through all kinds of experiences, moods, pleasures and pain. I know it very well and I cling to that. Can I also know in the same way as I know this area, this thing called death? If I know both then there is no problem. Can I know, as I know living, what death means? I have accepted living, with the pain, the dirt and squalor, the brutalities, starvation, everything – I know what all that means. Can I also know this enormous mysterious thing called death? By asking that question I am going to find out, inquire. I have really never inquired into living, into this whole process of existence. I have accepted it, I have suffered in it, I have gone through hell with it. Can I also know this thing called death, investigate it? I have accepted living and I have accepted death, but never investigated. So we are going to investigate both, the living and the dying.

Is all existence, all living this battle? Battle means pleasure, pain, all that. In inquiring, I see that is not living, that it is a terrible state to be in. I have investigated it, I have explored it, and I say: why should human beings live this way? This is so totally wrong. I will find a way of living entirely different from that. My investigation into living has shown me that the way one lives and thinks has no meaning. And by investigating very, very deeply, I find out that there is an entirely different meaning. I find out for myself, I have gone into it. And I say I must also inquire into death, I must find out what it really means – not be frightened, not put it away, not have explanations; nothing. I am going to inquire, find out. I have been frightened of death because I have never inquired into it, found out what it means. So I have gone into it. Now my mind has inquired into the living and what it means to die. So it says both living and dying are the same.

Have you enquired deeply into the meaning of living? I know you have accepted living as pain. Is that living?

Q: You have to die to it.

K:No, don’t die to anything, just watch it, inquire, find out. You have got a mind, you have got tremendous experience, you have got all kinds of knowledge, find out whether this is living, this terrible thing man has made of life. That is not living. And you can find the meaning of living only when you discard totally the structure which man has put together. So if you do not find the meaning of living deeply, and therefore merely accept existence as it is, you are incapable of inquiring into death. Because in the inquiry into living you will find how to inquire into death. They are not two separate things. The life that you lead, is that living? Is that a way of an intelligent, sane, human being? Is that the way to live? What do you say?

Q: It is not living.

K: All right, if it is not living what are you going to do about it? Do you accept this way of living? If you don’t, what is the next step?

Q: I want to find out another way of living.

K: You want to find another way of living. How do you find out? If this is not the way of living and you want to find another way of living, how do you find out? You can only find out through inquiry, which means a mind that is capable of looking without any direction or motive. When you have a motive it is directed and therefore distorted. So a mind that inquires into living must have no motive in inquiry and is therefore free to inquire, like a scientist who doesn’t come with a motive but only looks at what is taking place under the microscope.

I will not accept this way of living under any circumstances; I don’t want to live that way. Therefore my mind askes how it is to inquire into this; is there a different way of living? To find a different way of living and therefore a different meaning of existence, I must come to it with a mind that is not prejudiced, not frightened, doesn’t know what is going to happen, but is going to find out. That means a mind that has no fear of what it is going to discover.

So in the same way the mind has to enquire into death. If you are frightened it can’t inquire. If you say, ‘I must survive, I must have a next life become a little better,’ it has no meaning. So the mind must be capable of inquiring without a motive and without fear. That is the primary importance in inquiry: no motive and no fear. Please don’t accept a thing that the speaker is saying. He has no authority. He is not your guru. You are not his followers. We are inquiring.

The way we are living has no meaning and I want to find out what is the meaning of living, if there is a different way of living. I see there is a different way of living when there is no division in action, in thought, in the observer and the observed. I see thought has made the world what it is, and I am part of that world and that world is me. Thought is responsible. So I am concerned now with the investigation of thought. I see thought is necessary otherwise I can’t speak or drive a car. Thought is necessary to function in a factory or business. Thought is necessary in the employment of the knowledge which I have acquired. I see in that area thought is necessary. But I see thought is totally unnecessary in relationship, with its image. Therefore is it possible to live with thought functioning in a certain area and thought not functioning in relationship? Because thought is not love.

The mind must be capable of inquiring without a motive and without fear.

So I have found something. I have found a deep meaning. I have found a way of living where thought functions normally, objectively, logically, sanely, and there is no psychological movement at all, the psychological movement as the “me” which is put together by thought, by words, by experience, by knowledge. So the psychological entity is not. I see that is the way to live, for knowledge to function efficiently without the psychological element projecting into the field of knowledge. As long as there is the “me”, the self, there will be a battle. The self is put together by thought: the word, remembrance and attachment are the basis of thought. So I have discovered that that is the way to live, not as an idea but as an actuality. If you live that way, if you have inquired, gone into it profoundly, then it is yours. Then we have relationship and then it is real fun, a great delight to discuss and talk over the real thing.

In the same way I want to inquire into what is death. I don’t know what it means. I know what people have said about it. My son has died, my wife, husband. I have shed tears, felt loneliness, the misery, the appalling sense of wastage of life. So I am going to find out what death means. Can my mind inquire into something that it doesn’t know? I don’t know what death means. I have seen death touch every life from the poorest to the most famous, from the most indulgent, stupid, superficial man to he who thinks he is very deep. Death has touched everybody. So I am going to find out. My mind asks, what is death? I am not frightened. That is the fundamental thing in inquiry. And having no fear I have no beliefs about whether the entity lives or does not live after dying. The “me” is afraid of death; the “me” is the known. The “me” is attached to furniture, a house, the family, to the name, the country, and that “me” is frightened when it inquires into death because it says, ‘I may come to an end.’ I don’t mind my body coming to an end, only that inward sense of the “me”. And so one has given lots of names to it: the soul, the atman, and so on – all put together by thought.

Q: I see all this intellectually, but fear exists.

K: That’s it. I see it but fear goes on. What does that mean? You don’t say when you see a danger, ‘I see danger’ and go on with the danger, do you? When you hear a statement you translate it into an idea, which everybody does, and then there is a division between the idea and what is. If you could listen without the formulation of an idea or a conclusion, then there is only what is. Can you listen without forming a conclusion?

Q: It is very difficult.

K: That is real active inquiry.

So the mind sees that the “me” is not permanent but is just put together by transient thought. The “me” is just a series of words and memories, which have no substance or reality. So the mind now is not frightened and it is going to inquire into what death means. What does death mean? Dying to the known? What happens when the mind doesn’t die to the known? The known is the “me” with all its structure and its misery. If the mind doesn’t die to that known it goes on like a stream. In that stream all human beings are caught. We never say there must be an ending of the known, but accept it. We are caught in that stream of so-called life which continues because the mind has never pulled itself out of it. So in a séance with mediums, when there are manifestations of your husband or wife or children, it is from that stream. As long as you are caught in that trap, in that stream, you may die but that stream is the world and the world is you. So when you get in touch with your elder brother when he is dead, it is there, from that stream. One who is free of that stream can never be caught by a medium.

What does it mean to die? I have seen death. I know I will die. The organism will die. Misused for so many years through drugs, drink, indulgence, the misery of disease, pain, and ending up being drugged, it may be kept alive for a few years longer but I know the organism will die. Is that what the mind is frightened about? Is it frightened about losing the identity with the furniture. The furniture is the wife or husband, the book, the photograph, the money, all that. So the mind asks, ‘What am I attached to the furniture for?’ I am using that one word, furniture, to convey the whole of the urge to possess, attachment, domination. Why does the mind desire identification with something? Is it because it has to be occupied with something? Occupied with the house, with sex, with knowledge, it doesn’t matter what it is, it has got to be occupied, because if it is not occupied what takes place? Occupation of every kind is the same; there is no noble or ignoble occupation. When the mind is occupied it feels it is alive, it is moving, it is working, it has a sense of reality, but when I am not occupied, what happens?

Q: It doesn’t exist.

K: Wait. You haven’t explored it, you have already come to a conclusion. Why is the mind occupied? What happens to the mind that is not occupied? Have you found that out?

Q: It sees.

K: Have you found out for yourself what happens to a mind that is not occupied?

Q: It is empty.

K: How do you know?

Q: It is empty when it is not occupied.

K:You are dealing with ideas, not with the actuality of a mind that has explored, gone into what happens to a mind that is occupied, what happens to a life that is occupied with pain, pleasure, with success, boredom, with loneliness, problems. If it is not occupied with problems, is it an empty life? If it is not occupied with pain, pleasure, with your gods, and all the rest of it, is it a deteriorating life?

Q: No.

K: Don’t say no; you don’t know about it. You are just indulging in words. When the mind is not occupied is that an empty mind, a dull mind, a deteriorating mind? Find out, test it for yourself. If you are not occupied what happens? It picks up another occupation, doesn’t it? What happens if I am not occupied about anything?

What happens to a mind that is not occupied?

So you are occupied and you die being occupied. And that you call living. Therefore dying and living is occupation. You never say, ‘I know I am occupied, I will find out what it means not to be occupied.’ You are occupied because occupation is one of the activities of the mind which is the “me”. Occupation is a form of identification and that gives me the feeling that I am alive; the “me” is fully active. Now I have looked at it and I have seen what a terrible thing occupation is. I have seen it, not just verbalised it. Therefore what happens to a mind that is not occupied?

Q: Perhaps something new.

K: Sir, I am hungry and you give me words to eat. I don’t want your words, I want food. You are filling your hunger with words. I want to find out what happens to a mind that is not occupied – ever, not just one occupation. What is a mind that is occupied, and what happens to it if it is not? What happens to a mind that has inquired into life and living? Living which has been so occupied from morning to night, and at night dreaming and the interpretation of those dreams. It has been occupied endlessly, never a moment of non-occupation. And it is also occupied with death and what will happen – there too there is never a moment of non-occupation. So the inquiry is: what happens when the mind is not occupied at all? What takes place? Is it emptiness? That emptiness, is it degenerating? Is there emptiness at all, or there is only observation and nothing else? That observation is not the occupation of the observer occupied with the observed. If there is only observation then what takes place? Is there anything to observe, or there is absolute nothing? Everybody fears to be absolutely nothing. And because you want to be something you are occupied with everything. All your problems arise from that.

Now if you have gone into it with the speaker, you will see that life and love and death are the same thing. And the understanding of it is the understanding of that extraordinary thing called life – living entirely differently, without occupation and therefore without conflict. And a mind that is not in conflict is free from death.

Krishnamurti in Saanen 1973, Discussion 6

Video: Silence as the Ground of the Eternal

There is a state which is timeless and therefore incredibly vast. This is something most marvellous if you come upon it. I can go into it, but the description is not the described. It is for you to learn by looking at yourself. No book, no teacher can teach you about this. Don’t depend on anyone, don’t join spiritual organizations; one has to learn this out of oneself. And there the mind will discover things that are incredible. But for that, there must be no fragmentation and therefore immense stability, swiftness, mobility. To such a mind there is no time and therefore this whole concept of death and living has quite a different meaning.

From Krishnamurti’s Book THE IMPOSSIBLE QUESTION