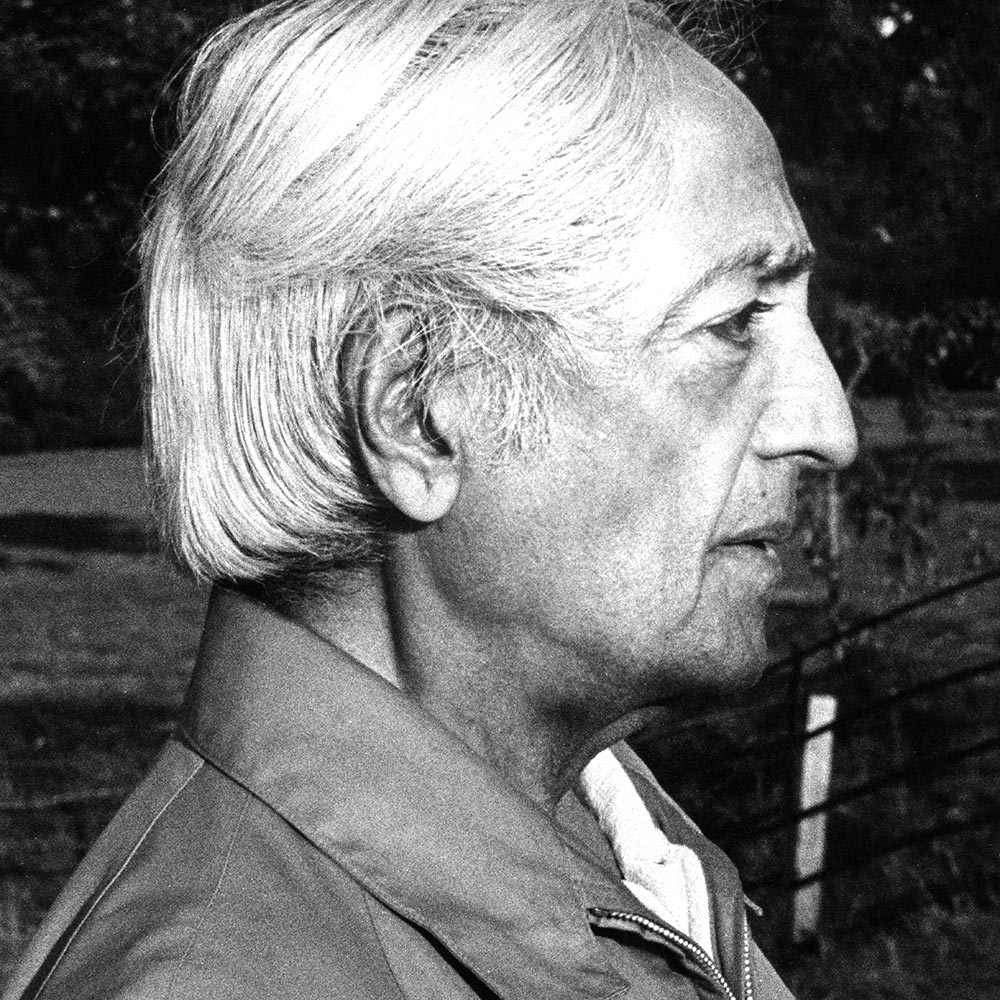

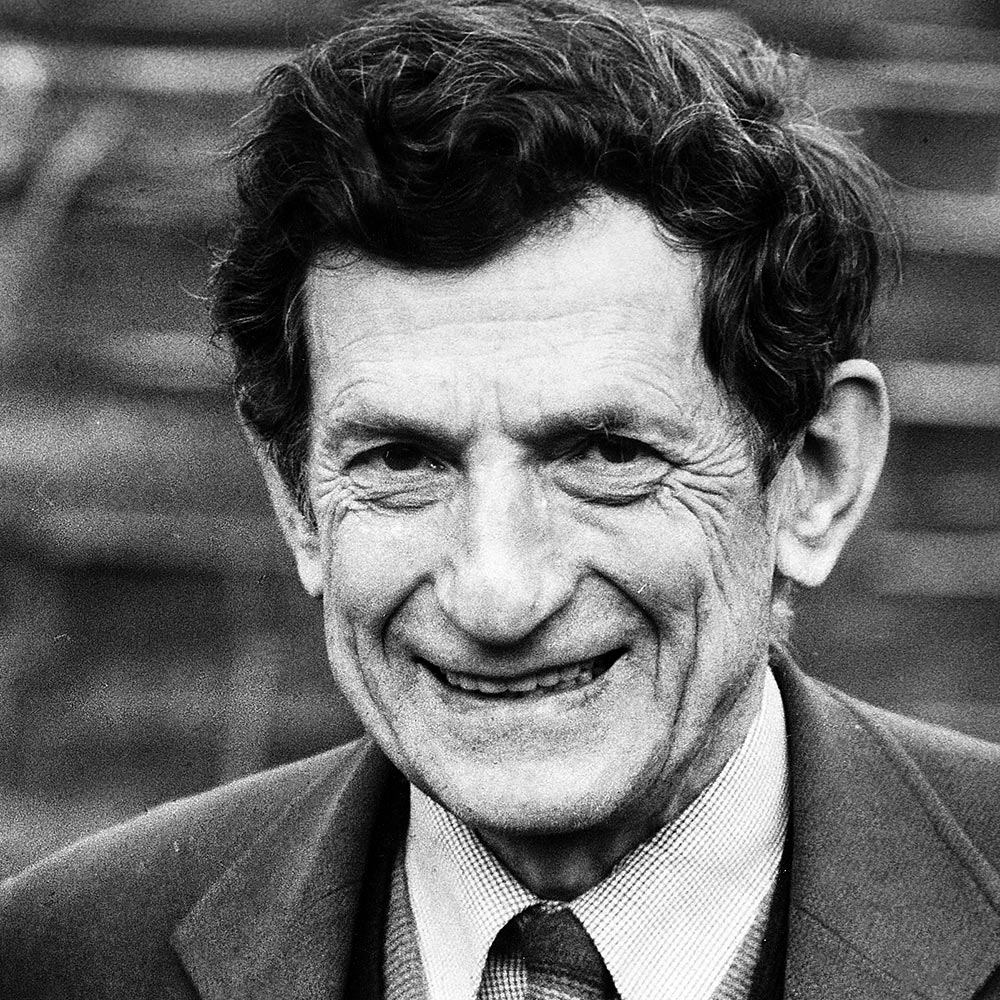

As the fire of interest and enthusiasm for Krishnamurti’s work took hold in England, a new relationship was formed, one which was of importance to physicist David Bohm as well as Krishnamurti himself.

Bohm was a man of vast intellect, capable of exploring questions in depth, yet with a scientist’s tentativeness. During the war years he worked on the ‘scattering of nuclear particles’ under the supervision of J. Robert Oppenheimer. He became assistant professor at Princeton University in 1946, where he began discussions with Einstein. He left the US to work in Brazil and Israel, and later settled in London as professor of theoretical physics at Birkbeck College.

The meetings with Krishnamurti became legendary and gave renewed urgency to the term ‘dialogue’ as a fundamental of Krishnamurtian teaching. ‘Exploring together, like two friends sitting under a tree,’ or ‘thinking together’ is the way this process has been described. However one would characterize it, dialogue is an old yet new way at looking at and questioning the human condition.

Evelyn Blau: Dr. Bohm, could you say how you first came into contact with Krishnamurti or his teaching?

David Bohm: The background is that in my work in physics I was always interested in the general philosophical questions as they related to physics, and more generally, universally as it might relate to the whole constitution of nature and of man. One of the points arising in physics which is somewhat related to what Krishnaji is doing, is in quantum theory, where you have the fact that energy is found to be existent as discrete units which are not divisible.

EB: Could you clarify the word discrete in that context?

DB: One view is that matter is continuous, flowing, and the other view is it is made of atoms, which are discrete, but there are so many atoms that it appears to be continuous. Like grains in an hourglass, they flow as if they were water. But obviously they are made of discrete units. So the notion of the atomicity or discreteness of matter had already been common for many centuries, but in the early 20th-century there arose a discovery that energy is discrete as well. Energy comes in units, though they are very tiny; therefore, we don’t easily see them, and the number is so great that they appear to be continuous. Now this has important consequences because it means that things cannot be divided from each other. If two things interact by means of an energy that cannot be divided, that link is indivisible. Therefore, fundamentally, the entire universe is indivisible, and in particular, it means that the thing observed and the apparatus which observes it cannot be really separated.

We already had this point that the observer cannot be separated from the observed. In fact, whenever you observe, the thing observed is changed because it cannot by this interaction be reduced below a certain level. Therefore, you have the transformation of the object observed in the act of observation. I had already noted the similarity to consciousness: that if you try to observe your thought in any detail, the whole train of thought changes. That is clear. So therefore you cannot have the separation of the observer and the observed in consciousness. The observer changes the observed, and the observed changes the observer, therefore, there was a mysterious quality which was not really understood in physics.

EB: Was this part of your observation, scientifically, as well as philosophically, when you first came in contact with Krishnamurti?

DB: That’s right, let me add one more point. My interest in physics… I had always had a tendency to say that what I was thinking about in physics should be taking place within me. I felt that there was a parallel between what is in consciousness and what is in matter in general, and I felt movement was also a question, that the movement that you see outside, you feel inside. In general therefore, I felt that we directly apprehended the nature of reality in our own being.

EB: Had you pursued this through contacts with other teachers, or philosophers, or was this a purely scientific matter and your own self-observation?

DB: At that point, it was probably mostly my own. The question of the observer and the observed was obviously looked at in quantum mechanics as to its implications, especially by Nils Bohr, who in fact was influenced by the philosopher William James. He had developed an idea of the stream of consciousness, along the lines I have been saying. But as a matter of fact, that idea occurred to me independently as soon as I read about quantum theory. There was an analogy between this stream of consciousness and the behaviour of matter. That was the background of my interest in science. I was also trying to understand the universal nature of matter. Questions like causality and time and space, and totality, to grasp it all.

If you try to observe your thought in any detail, the whole train of thought changes.

EB: Is this something that is shared by other scientists, are there similar observations?

DB: Those who are inclined that way do, but most do not. Most scientists are very pragmatically oriented, and mainly want to get results. They would like to make a theory that would predict matter accurately and control it, but a few are interested in this question. Say Einstein. I should say that I had some discussions with Einstein on the quantum theory when I was in Princeton. Most physicists know the quantum theory cannot be understood, they take it as a calculus, as a way of getting results, predicting. They say, ‘That is all that really matters, and that a deeper understanding might be nice, but it is not really essential.’

EB: So with the background of this kind of interest, you came to reading a book by Krishnamurti?

DB: Yes. As I said, scientists have an interest in cosmology, many of them are trying to get a grasp of the totality of the cosmos. Einstein particularly wanted to understand it as one whole. What happened in regard to Krishnamurti was that my wife and I were in Bristol, UK. We used to go to the public library where I got interested in philosophical or even mystic or religious books, such as those of Ouspensky and Gurdjieff because I was somewhat dissatisfied with what could be done in the ordinary sphere. My wife Saral and I came across The First and Last Freedom. She saw a phrase there, the observer and the observed, so she thought it might have something to do with quantum theory, and she pointed it out to me. When I read the book, I was very interested in it. I felt it was a very significant one, and it had a tremendous effect on me, that the questions of the observer and the observed were brought to the psychological level of existence, and I had the hope that one could tie up physics and psychological matters. I also read the Commentaries on Living. They were the only other books in the library. I wrote to the publisher in America, and asked whether one could get more books, or whether Krishnamurti was around. Somebody sent me a letter suggesting that I get in touch with the people in England. I wrote to them and they sent me a list of books.

EB: Do you remember what year that was?

DB: It could have been about 1958, or 1959. Then somewhere around 1960, he came back to England and gave talks. It could have been 1960. In my letter ordering books, I asked if Krishnamurti ever came to England, and they said he was coming and there would be a limited number of people who could come to hear him. I came with Saral and, while I was here I wrote a letter asking if I could talk with Krishnamurti, and then I got a phone call arranging to make an appointment. They were renting a house in Wimbledon, and I waited for him with Saral. Then he came in, and there was a long silence, but then we began discussing. I told him all about my ideas in physics, which he probably couldn’t have understood in detail, but he got the spirit of it. I used words like totality, and when I used this word totality, he grabbed me by the arm, and said, ‘That’s it, that’s it!’

EB: You had read books by Krishnamurti. What was your initial impression as you first met this man?

DB: I don’t usually form those impressions, I usually just go ahead. But the impression I got was that when we… you see we remained silent, which was not usual, but it didn’t seem odd to me at the time, and there was no tension in it. Then we began to talk. In talking I got the feeling of close communication, instant communication, of a kind which I sometimes get in science with people who are vividly interested in the same thing. He had this intense energy, openness, and clarity, and a sense of no tension. I can’t remember the details but he couldn’t understand very much of what I said, except the general drift of it.

EB: You were speaking on a more scientific level?

DB: I was speaking about the questions I was talking of earlier, like quantum theory and relativity, and then raising the question of whether the totality can be grasped. I should also say that my interests had turned toward understanding thought. I gradually began to see that it was necessary to understand our thought. In going into philosophy, and going into causality and questions like that, it was a matter of how we are thinking. I had earlier been influenced by people who were interested in dialectical materialism and I talked to a man who had read a lot of Hegel and raised the question of the very nature of our thought. Not merely what we are thinking about, but the structure of how our thought works, and that it works through opposites. Our thought inevitably unites the two opposite characteristics of necessity and contingency. Another man I met said I should pay attention to my thought, how it is actually working. So I had become very interested in how thought proceeds, considering thought as a process in itself, not its content but its actual nature and structure.

EB: So you found similarities between what Krishnamurti was saying, and someone like Hegel.

DB: There is some similarity, yes. I found a relationship, and that was the reason I was fascinated by Krishnamurti. He was going very deeply into thought, much deeper than Hegel, in the sense that he also went into feeling and into your whole life. He didn’t stop at abstract thought.

I had become very interested in how thought proceeds, considering thought as a process in itself, not its content but its actual nature and structure.

EB: So over a period of years you became deeply acquainted with Krishnamurti’s thought. In the course of that how did you look at the source of Krishnamurti’s teaching?

DB: I didn’t raise the question for a while. What happened was that we began to meet every time he came to London and had one or two discussions. In the first year I wanted to discuss the question of the universal and the particular with him, and we raised the question, ‘Is mind universal?’ and he said yes. We had quite a good discussion on that. When we left I had the feeling that the state of mind had changed, I could see that there was no feeling, but clarity.

EB: When you say the state of mind had changed, do you mean both of your states of mind?

DB: I don’t know, I assume that he was similar since we were in close communication. I said that I had no feeling, and he said, ‘Yes, that’s right,’ which surprised me, because I had previously thought that anything intense must have a lot of feeling. And then when I went out I had a sense of some presence in the sky, but I generally discount such things saying that it’s my imagination.

EB: Was that a physical sense?

DB: Yes.

EB:You actually could see some…

DB: Feel. Not see anything there but feel something there, something universal.

EB: Had you ever felt anything of that nature before?

DB: I had hints of that, but my whole background was such as to say, I didn’t tell my parents or anybody, they would have said, ‘You’re just imagining that.’

EB: Did you feel that there was any relationship between the intensity of your discussion and what was happening?

DB: Yes, I probably felt that they were related. In fact I might have explained it by saying I was projecting the universality into the sky, as I might have done as a child.

EB: When was your next meeting?

DB: I didn’t see a lot of him but we had discussions every year in London when he came in June, and when I went to Saanen. We began to have discussions in which at least for a while I could feel that was some change of consciousness, but by the time I got back to England it went away. When you go back into ordinary life.

EB: What would you say are the salient characteristics or qualities of his teaching that differentiate it from that of others?

DB: First of all the total concern with all phases of life and consciousness, and secondly the question of something beyond consciousness, which began to emerge in our discussions in Saanen.

EB: Did Krishnamurti ever describe any particular influence on his teaching? He says that he doesn’t read books of a religious or philosophic nature, but in his earlier years he may have come into contact with that.

DB: He didn’t describe it to me, but I have heard people say that he read The Cloud of Unknowing, which was influential, and probably other books. My feeling is that he must also have been familiar with what the Theosophists were saying. The other things he’s read or heard may have awakened him to some extent.

EB: Did you ever feel that he was drawing you away from your scientific interests?

DB: No, because I was going on with my scientific interests. At that time I wanted to understand this whole question of the observer and observed scientifically, and the question of dealing with the universe as a totality. So it didn’t really draw me away from the scientific work. I became more and more interested in the question of the nature of thought, which is crucial in everything, including science, since it was the only instrument you had. When I was in London with Krishnaji, I did discuss what to do about scientific research, and I remember he said, ‘Begin from the unknown. Try beginning from the unknown.’ I could see that the question of getting free of the known was the crucial question in science, as well as in everything. For example, scientific discoveries. You may have heard of Archimedes and his discoveries. He was given the problem of measuring the volume of a crown of irregular size in order to see whether it was gold or not by weighing it, and it was too irregular to be measured and he was very puzzled, and then suddenly when he was in his bath he saw the water displaced by his body, and he realized that no matter what the shape, the water displaced is equal to the volume of the body. And therefore he could measure the volume of the crown. He went out shouting ‘Eureka!’ Now, consider the nature of what went on. The basic barrier to seeing was that people thought of things in different compartments, one was volume by measurement, and two, water being displaced would have nothing to do with that. To allow those to be connected, the mind would have to dissolve those rigid compartments. Once the connection was made, anybody using ordinary reasoning could have done the rest, any schoolboy of reasonable intelligence. The same happened with Newton. Obviously Archimedes as well as Newton and Einstein were in states of intense energy when they were working, and what happens is that the moment of insight is the dissolving of the barrier in thought. It is insight into the nature of thought, not into the problem. All insight is the same. It is always insight into thought. Not its content but its actual physical nature, which makes the barrier. And that is what I think Krishnamurti was saying, that insight transforms the whole structure of thought and makes the consciousness different. For scientists that may happen for a moment, and then they get interested in the result, working it out, but Krishnamurti is emphasizing insight as the essence of life itself. Without coming to a conclusion. Don’t worry too much about the results, however important they may be. Insight, fresh insight is continually needed. That insight is continually dissolving the rigid compartments of thought. And that is the transformation of consciousness. Our consciousness is now rigid and brittle because it’s held in fixed patterns of thought due to our conditioning about ourselves, and we get attached to those thoughts, they feel more comfortable.

Krishnamurti is emphasizing insight as the essence of life itself.

EB: Krishnamurti always seems to be able to make the distinction between using thought as a tool and then putting it aside when the tool was no longer needed for a specific reason. Putting it aside leaves space for further inquiry.

DB: Yes, one could feel this space was present in our discussion.

EB: What would you say are the most characteristic features of Krishnamurti’s teaching?

DB: I think there are several features you could say are characteristic. The emphasis on thought as the source of our trouble. Krishnamurti says that thought is a material process. He’s always said that. Most people tend to regard it as other than that, and I don’t see that emphasized anywhere. It’s very important to see that thought is a material process, in other words, thought can be observed as any matter can be observed. When we are observing inwardly we are observing not the content of thought, not the idea, not the feeling, but the material process itself. If something is wrong with thought it’s because erroneous things have been controlled in memory which then control you, and the memory has to be changed physically. With a tape you could wipe out the memory with a magnet, but you would wipe out the necessary memories along with the unnecessary ones.

EB: Krishnamurti seems to indicate that a certain tabula rasa can be achieved through clear perception.

DB: That’s right, but it’s necessarily happening intelligently, so that you do not wipe out the necessary memories but you’ll wipe out the memories which give rise to the importance of the self. He says that there is an energy beyond matter, which is truth, and that truth acts with the force of necessity. It actually works on the material basis of thought and consciousness and changes that into an orderly form. So it ceases to create disorder. Then thought will only work where it is needed and leaves the mind empty for something deeper.

EB: People often raise the point that they lack sufficient energy to continue this investigation in their daily lives. How would you respond to that?

DB: That’s probably because there is not an understanding of the nature of energy. Let’s connect it with another objection people raise. They see it at certain times, but it goes away.

EB: That’s a frequent complaint.

DB: You have to see what is essential and universal, and that will transform the mind. The universal belongs to everybody, as well as covering everything, every possible form. It is the general consciousness of mankind. We come now to energy, this whole process of the ego is continually wasting energy, getting you low and confusing you.

EB: In other words, the individual’s perception of themselves as a separate being, is a waste of energy.

Thought can be observed as any matter can be observed.

DB: Yes, because if you see yourself as a particular being you will continually try to protect that being. Your energies will be dissipated.

EB: Earlier you were saying that since thought is a material process, it is necessary to observe the process of thought rather than its contents. How is one to do that? How is one to make that shift and observe the material process when it appears as if the only thing that consciousness is aware of is content?

DB: Before we get to that, another important difference of Krishnamurti is his emphasis on actual life, on being aware of everything, and also his refusal to accept authority, which is really extremely important. There are Buddhists who say that Krishnamurti is saying much the same as the Buddhists, but he says why begin with the Buddha, why not begin with what is here now? That was very important, he refuses to take seriously the comparison with what other people have said. Now to come back to what you were saying, about observation of the material process. You have to see what can be observed about thought aside from the pictures and feelings and its meaning. Whatever you think appears in consciousness as a show. That is the way thought works to display its content, as a show of imagination. Therefore if you think the observer is separate from the observed, it is going to appear in consciousness as two different entities. The point is that the words will seem to be coming from the observer who knows, who sees, and therefore they are the truth, they are a description of the truth. That is the illusion. The way a magician works is exactly the same. Every magician’s work depends on distracting your attention so that you do not see how things are connected. Suddenly something appears out of nothing but you do not see how it depends on what he actually did.

EB:: You miss that missing link.

DB: By missing the link you change the meaning completely.

EB: So what appears to be magic is actually not realizing the connection of all of these links.

DB: Yes, and that kind of magic takes place in consciousness, the observer and the observed see things appear and the observer appears to be unlinked to the observed. Therefore it comes out as if from nothing. And if it came from nothing it would be truth. Something that suddenly appears in consciousness out of nothing is taken as real and true. If you see the link to thought then you see it as not all that deep.

There is an energy beyond matter, which is truth, and that truth acts with the force of necessity.

EB: You’re saying then that thought is more shallow than we believe it to be.

DB: Yes, in fact it is extremely shallow. Most of our consciousness is very, very shallow.

EB: And what we see as our most profound insights are really rather superficial observations.

DB: Yes, or not even observations. Many of them are just delusions, a great deal of what we think about ourselves is just an illusion. The analogy that is often made in Indian literature is if you have a rope that you think is a snake, your heart’s beating, your mind is confused, and the minute you see that it is not a snake everything changes. The mere perception is enough to change the state of mind, and the perception that, for example, the observer and the observed are not independent, will mean that the things which the observer is thinking are not regarded as truth anymore. They lose that power. Now if you see the whole… you could say the whole energy of the brain is aroused and directed by the show which thought makes of its content, it is like a map. There is a show in which this whole content is regarded as truth, as necessary. Then the entire brain is going to restart up around this show. Everything is going to be arranged to try to make a better show. Now the minute you see it is only a show, this all stops. Now the brain quiets down and it is in another state. It is no longer trapped and therefore it can do something entirely different. But to do that it is necessary not merely to say so but to see it in the way we have been suggesting.

I thought of another case where you can see the power of perception. It was this case of Helen Keller – you may have heard of her, she was blind, deaf, and dumb. When she couldn’t communicate she was rather like a wild animal. They found this teacher, Ann Sullivan who played a game, as it were, to put the child’s hand in contact with something, that was her only sense, and scratch the word on her hand. First it was clearly nothing but a game – she didn’t understand what was going on. Then Helen Keller recalls that one morning she was exposed to water in a glass and the name was scratched, and in the afternoon to water in a pump, and the name was scratched, and suddenly she had an insight, a shattering insight, and it was that everything has a name. If water was one thing in all its different forms, this one name, water, could be communicated to the other person who used the same name. From there on she began to use language and in a few days she learned words. In a few days she was making sentences and her whole life was transformed. She was no longer this violent wild person but entirely different. So you can see that this perception transformed everything. Once she had the perception there was no turning back. It was not to say she had the perception and then forgot about it and had to have it again. And I think Krishnamurti is implying that to see that the observer is the observed would be a perception enormously beyond what she had. It would have a far more revolutionary effect.

EB: You feel then that the concept of the observer and the observed is a key one in Krishnamurti’s teachings.

DB: Yes, in fact they are identical.

EB: I wonder if you would recapitulate some of the other key factors in his teaching.

DB: The question of time, psychological time being merely produced by thought. Time is just the same thing as the observer and the observed. The ending of the observer and the observed is identical with the ending of psychological time and therefore a timeless state comes.

EB: And with the perception of the observer and the observed as one, all of the phenomena of suffering, the human difficulties that we all go through are ended.

DB: That’s right, because they all originate in ignorance of the true nature of this question. Then the emphasis on compassion arises. Passion for all, not merely passion for those who are suffering. That is part of the passion which goes beyond suffering.

EB: Authority is certainly another major factor in his teaching.

The observer and the observed are not independent.

DB: Yes, you can see now why authority is so important. One of the points you have to add is the enormous power of the mind to deceive itself, which he recognized. Authority is one of the major forms of self-deception. There is authority in the mind, not authority in other matters, they are not necessarily self-deception. If somebody comes out as an authority on truth, the danger is that you say that you had begun to doubt certain things yourself, but now you take what he says as true. Because you want it to be so. It is basically that truth must be for me what I need it to be. I feel uneasy, frightened, worried, and so on, and so the authority, the religious authority, comes along and says that God will take care of you as long as you are good and you believe, and so on. Therefore I want to believe and therefore I say that that’s the truth. I was on the point of having to question all this and along comes the authority who makes it unnecessary. You have to ask why you accept authority. The authority gives you no proof whatsoever, so why do you accept it? Because you want to, you need to. I must have comfort, consolation and safety. And here comes this impressive figure, very nice looking, perhaps clothed in certain ways with certain ceremonies, and very nice music and consoling thoughts and a good manner, and says, ‘You’re alright, everything is going to be all right. You just have to believe.’

EB: One of the major characteristics of authority is that it has great power, and that power displays itself, as you said, in ritual and ceremony. Just as a worldly power, a king, would show himself through his trappings through his crown, etc.

DB: That’s right. But you see, it is an empty show. The whole point is that authority builds an empty show of power around itself. A display, as you called it. There is nothing behind it whatsoever, except our belief that it is there.

EB: Have you been able to observe in Krishnamurti’s writings any breaking point where his teaching deviated or went in a completely different direction?

DB: No, I can’t see any fundamental change.

EB: Even as a young man, this teaching was implicit within everything he said.

DB: Yes, yes.

EB: And there was no learning from other models?

DB: No. I think it comes from a source beyond the brain which is, in principle, open to everybody.

From the Book KRISHNAMURTI: 100 YEARS