I am this, and does an ideal make me struggle to become ‘that’? Is the ideal the cause of conflict?

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 1

Read More

I am this, and does the ideal make me struggle to become ‘that’? Is the ideal the cause of conflict? Is the ideal wholly dissimilar from what is? If it is completely different, if it has no relationship with what is, then what is cannot become the ideal. To become, there must be relationship between what is and the ideal, the goal. You say the ideal is giving us the impetus to struggle, so let us find out how the ideal comes into being. Is not the ideal a projection of the mind?

An ideal is your own projection. See how the mind has played a trick upon itself.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 1

Read More

An ideal is a marvellous and respectable escape from the actual.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 2

Read More

I am angry and the ideal says, ‘Don’t be angry.’ I suppress, control, conform and approximate myself to the ideal, and therefore I am always in conflict and pretending.

Krishnamurti, The Flight of the Eagle

Read More

The ideal of non-violence does not free the mind from violence.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 3

Read More

An ideal is the response of background and conditioning, so it can never be the means of liberating man from conflict and confusion.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 1

Read More

The truth is not an ideal or a myth, but the actual.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 1

Read More

The pursuit of an ideal excludes love, and without love no human problem can be solved.

Krishnamurti, Education and the Significance of Life

Read More

Freedom is at the beginning, not at the end; it is not to be found in some distant ideal.

Krishnamurti, Education and the Significance of Life

Read More

The right kind of education consists of understanding the child as he is without imposing upon him an ideal of what we think he should be.

Krishnamurti, Education and the Significance of Life

Read More

Working under the stimulus of authority – whether it be the authority of an ideal, or the authority of a person who represents that ideal – is not real cooperation.

Krishnamurti, Life Ahead

Read More

If action is imaginary, personal, according to an idea, a concept or an ideal, it ceases to be correct action.

Krishnamurti, Truth and Actuality

Read More

One must know oneself as one is, not as one wishes to be, which is merely an ideal and therefore fictitious, unreal. It is only that which is that can be transformed, not that which you wish to be.

Krishnamurti, The First and Last Freedom

Read More

When you see the falseness of an ideal, it drops away from you. You are what is.

Krishnamurti, Commentaries on Living 3

Read More

When you do not compare, when there is no ideal, no opposite, no factor of duality, when you no longer struggle to be different from what you are, what has happened to your mind?

Krishnamurti, Freedom From the Known

Read More

These quotes only touch on the many subjects Krishnamurti inquired into during his lifetime. His timeless and universal teachings can be explored using the Index of Topics where you will find texts, audio and video related on many themes. Another option is to browse our selection of curated articles or more short quotes. Krishnamurti’s reply when asked what lies at the heart of his teachings can be found here. Many Krishnamurti books are available, a selection of which can be explored here. To find out more about Krishnamurti’s life, please see our introduction and the biography. We also host a weekly podcast, and offer free downloads. Please visit our YouTube channel for hundreds of specially selected shorter clips. Below, you can learn more about Krishnamurti and our charity which he founded in 1968.

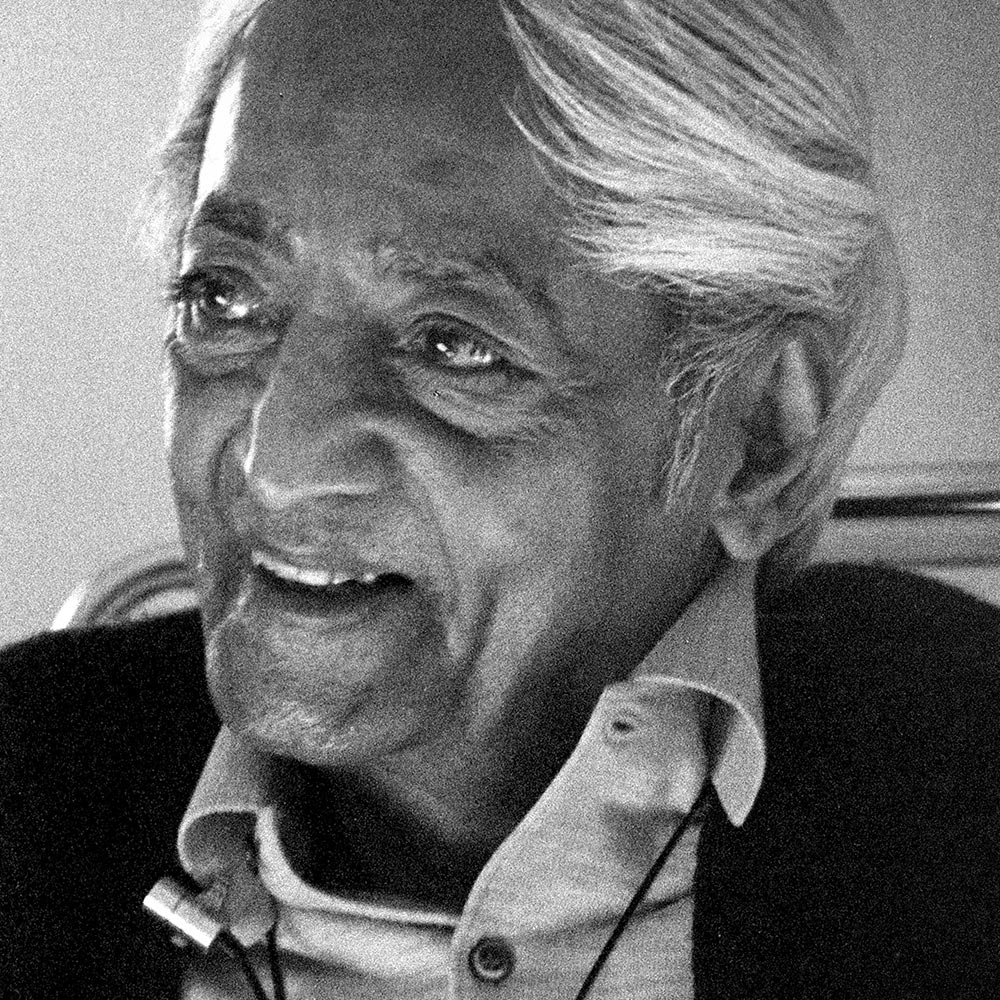

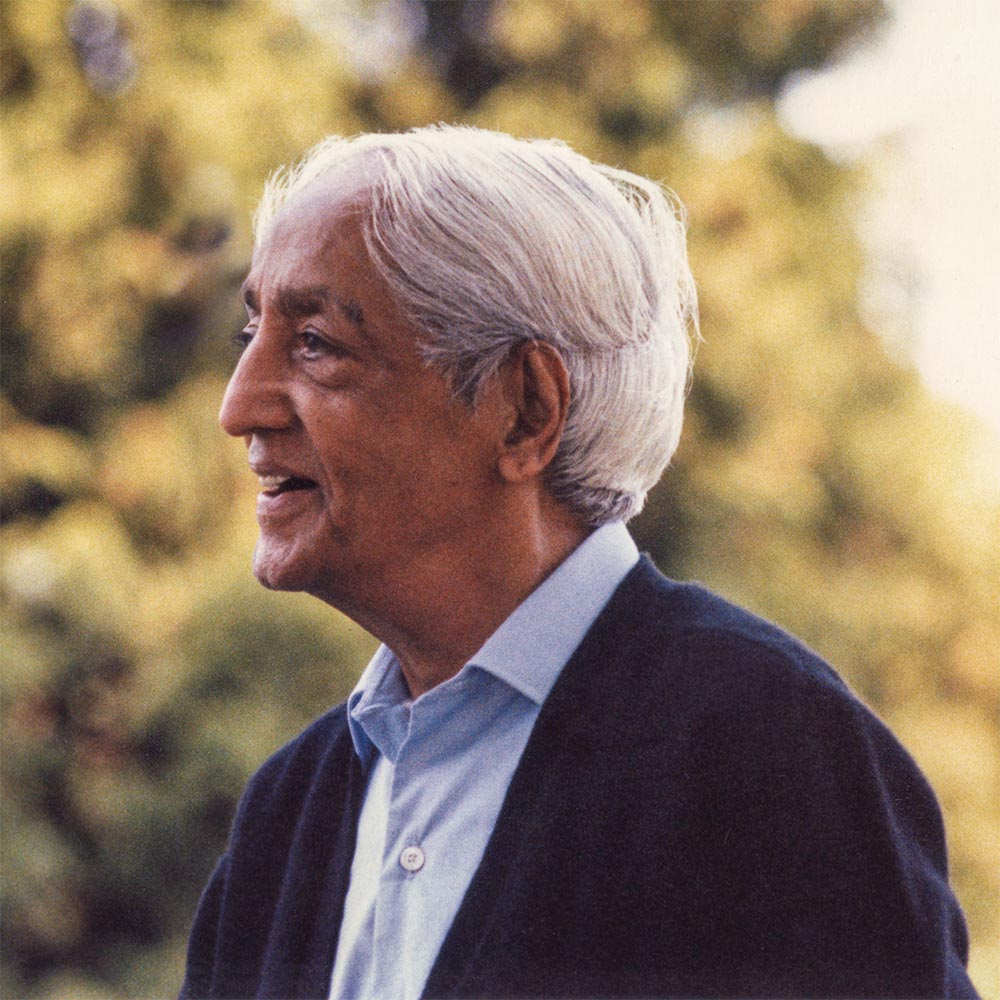

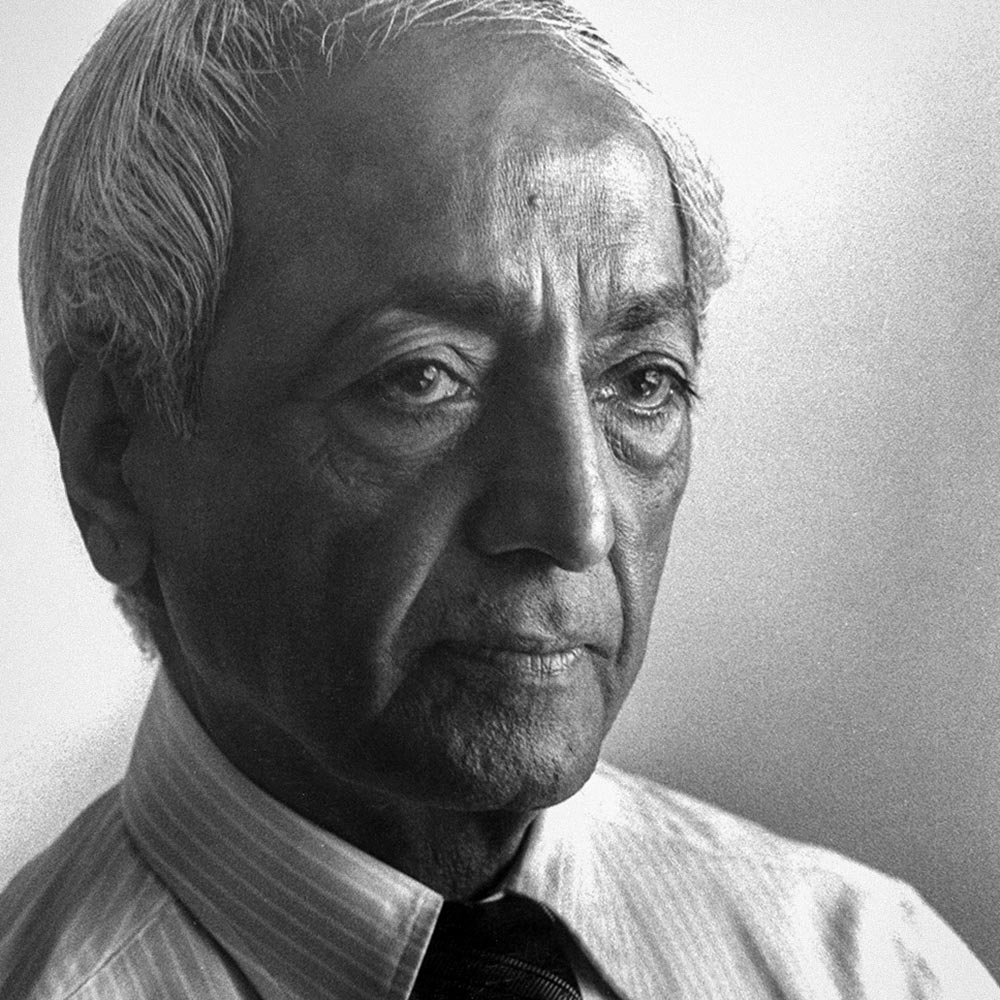

Who Was Krishnamurti?

J. Krishnamurti (1895-1986) is widely regarded as one of the greatest thinkers and religious teachers of all time. He spoke throughout the world to large audiences and to individuals, including writers, scientists, philosophers and educators, about the need for a radical change in mankind. Referring to himself, Krishnamurti said:

He is acting as a mirror for you to look into. That mirror is not an authority. It has no authority, it’s just a mirror. And when you see it clearly, understand what you see in that mirror, then throw it away, break it up.

Krishnamurti was concerned with all humanity and held no nationality or belief and belonged to no particular group or culture. In the latter part of his life, along with continuing to give public talks, he travelled mainly between the schools he had founded in India, Britain and the United States, which educate for the total understanding of man and the art of living. He stressed that only this profound understanding can create a new generation that will live in peace.

Krishnamurti reminded his listeners again and again that we are all human beings first and not Hindus, Muslims or Christians, that we are like the rest of humanity and are not different from one another. He asked that we tread lightly on this earth without destroying ourselves or the environment. He communicated to his listeners a deep sense of respect for nature. His teachings transcend man-made belief systems, nationalistic sentiment and sectarianism. At the same time, they give new meaning and direction to mankind’s search for truth. His teaching is timeless, universal and increasingly relevant to the modern age.

I am nobody. It is as simple as that. I am nobody. But what is important is who you are, what you are.

Krishnamurti

Krishnamurti spoke not as a guru but as a friend. His talks and discussions are based not on tradition-based knowledge but on his own insights into the human mind and his vision of the sacred, so he always communicated a sense of freshness and directness, although the essence of his message remained unchanged over the years. When Krishnamurti addressed large audiences, people felt that he was talking to each of them personally, addressing their own particular problem. In his private interviews, he was a compassionate teacher, listening attentively to those who came to him in sorrow, and encouraging them to heal themselves through their own understanding. Religious scholars found that his words threw new light on traditional concepts. Krishnamurti took on the challenge of modern scientists and psychologists and went with them step by step, discussing their theories and sometimes enabling them to discern the limitations of their theories.

Krishnamurti left a large body of literature in the form of public talks, writings, discussions with teachers and students, scientists, psychologists and religious figures, conversations with individuals, television and radio interviews, and letters. Many of these have been published as books, in over 60 languages, along with hundreds of audio and video recordings.

The Krishnamurti Foundation

Established in 1968 as a registered charity, and located at The Krishnamurti Centre, Krishnamurti Foundation Trust exists to preserve and make available Krishnamurti’s teachings.

The Foundation serves a global audience by providing worldwide free access to Krishnamurti videos, audio and texts to those who may be interested in pursuing an understanding of Krishnamurti’s work in their own lives.

In describing his intentions for the Foundations, Krishnamurti said:

The Foundations will see to it that these teachings are kept whole, are not distorted, are not made corrupt.